- Home

- The city

- The early Roman city

- The Saint-Jacques necropolis

- Funerary monuments

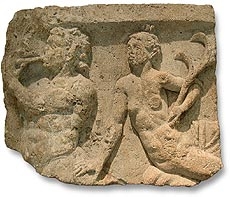

Partial funerary monument: two nude young men dancing. 3rd century. Reused in the foundation of a wall of the « Palace ».

Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Photo © A.-B. Pimpaud.

Funerary stele of an auxiliary cavalryman. Reused in the late Empire in the Saint-Marcel necropolis, 1868.

Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Sculpted block showing an armour breastplate and shields. Found reused in the Ile de la Cité, it was no doubt taken from a large mausoleum. Early Empire. Photo taken ca. 1863.

Musée Carnavalet, Paris. © BHVP.

Bas-relief featuring a Triton, blowing a horn or shell, and a Nereid; this was probably part of a mausoleum. Early Roman Empire. Reused in the decumanus to the south of the basilica at the Marché aux Fleurs, 1982.

Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Photo © A.-B. Pimpaud.

Steles

Some tombs possessed a funerary monument or a stele. A number of these steles have been found, not in situ but reused in Late Empire buildings or sarcophagi. The dead were depicted with symbols of their trade or an inscription that made mention of it. Steles mentioned the deceased's military career, like the one on this page showing an auxiliary cavalryman slaying the enemy with his spear, or inscriptions dedicated to a centurion, an exarch or a member of Menapii tribe.

Mausoleums

It is very likely that the necropolis contained mausoleums and large tombs. Historical texts, such as the one by the 17th century historian Henri Sauval, mention the discovery of such monuments. Large sculpted and decorated stone blocks that have been found reused in other places may have come from large mausoleums-some of the themes on them also appear in funerary contexts, such as the militia motif (life is a battle, with death marking the end). This is the case with the so-called "Mars disarmed by cupids" monument, or another adorned with shields and armour. A naval décor consisting of nymphs, tritons and sea panthers could be interpreted in the same manner. The artistic quality of some of these works and their skilful execution testify to the city's wealth and splendour under the Early Roman Empire.

Let us imagine a 2nd century traveler from Orleans-Genabum as it was known then-travelling to Lutetia along the Roman road that took the same direction as present-day rue de la Tombe-Issoire. On her left would have been the channel of the aqueduct and perhaps the arches that supported it. Upon reaching the level of the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Jacques, her first glimpse of Lutetia would be the magnificent and imposing funerary monuments that introduced the city and testified to the wealth of its inhabitants.

A mausoleum

In the 17th century, the historian Henri Sauval reported with amazement a distinctly monumental discovery.

In the preceding century, Carmelite nuns from Notre Dame des Champs

« digging there in order to build a chapel, encountered a cellar some fourteen feet down from ground level; in it, towards the centre, there was a man on horseback and two men standing. On a finger of the left hand of one of these men was the ring of a red clay lamp [.] that resembled a foot shod in a hobnailed shoe or perhaps the caliga clavata worn by Roman soldiers. He must have been a gambler, because in his right hand he carried a little cup shaped like a clay bowl that contained three tokens and three ivory dice as big as half a thumb, almost all fossilized, like the surrounding earth and stones. The small child held a ivory spoon with a foot-long handle in the fingers of his right hand, and seemed to want to place it in a large clay vessel near him, which was full of a liqueur so redolent that, since the recipient had been broken by accident, the air was laden with it. In his mouth as in the others' mouths was a bronze coin of Faustina the mother and Antoninus the Debonair, apparently for paying Charon's fee ».

Sauval H., Histoire et recherches des antiquités de la ville de Paris, Paris, 1724, 3 vol. [posthumous edition, published by Rousseau]; reprinted 1733-1750.

This is probably a sculptural group representing the deceased's cortege, on which were hung or placed the typical Roman objects described by Sauval.