- Home

- Archeology in Paris

- Fourteen centuries of discoveries

Arches of the Lutetian aqueduct in the Arcueil-Cachan valley in 1585-1586. Drawing by Arnold Van Buchel. © Utrecht Library.

Ancient graves discovered in the early 17th century on the site of the Hôtel d'Anjou. Drawing by Paul Petau. Bibliothèque de l'Institut. The meticulous care with which this "antiquarian" measured and drew archaeological objects renders this document still useful to archaeologists today.

Omens and legends in the Middle Ages

Literary texts from the Middle Ages tell us that discoveries of objects from antiquity were sources of legends. Grégoire de Tours, the famous 6th century chronicler, tells of the discovery of a bronze dormouse and serpent in a Parisian gutter; these were taken as omens that the city would be destroyed by fire. In the 12th century, the « arena » was described as "a large circus [.] whose ruins are immense". In the 14th century, walls that were demolished during the digging of a ditch were thought to be the work of the Sarrasins. We now know that they were part of the forum.

Antiquarians of the modern era

The desire to give a reasoned interpretation of the city's ruins appeared only in the modern era. Discoveries of tombs were widely reported, giving rise to a spirit of scientific enquiry. Henri Sauval, the first great historian of Paris, gave very detailed accounts of the excavation of tombs, mausoleums and inscriptions, and Paul Petau produced precise drawings of ancient tombs and their contents. Scholars also began to probe the nature of the ruins on the slopes of Montmartre, which they correctly thought to be of pagan origin. The discovery of the Boatmen's Pillar in 1710, with its dedication to Tiberius and the mysterious figures carved on it, gave rise to many theories-including one from Leibnitz himself. . Interest in monumental ruins spurred a number of investigations. The antiquity of the Cluny Baths was acknowledged, even if those who built it remained shrouded in legend-it was variously described as a palace of Caesar, Julian or the Merovingian kings.

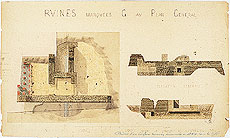

The Cluny baths prior to their excavation during the July Monarchy.

Engraving by Jean-Baptiste Jollois, 1843. © P. Cadet / CMN.

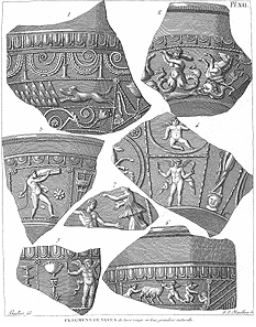

Roman houses, from the papers of Th. Vacquer.

© BHVP

Arretine ware discovered during the First Empire in the Luxembourg Gardens.

Engraving by Claude Grivaud de la Vincelle, 1807.

© P. Cadet / CMN.

19th century scholars

Under the Restoration and the July Monarchy, many scholars became interested in the archaeology of Paris. Among them was Dulaure, who was the first to identify a section of the Late Roman city wall, found during the demolition of a church on the Île de la Cité. The most remarkable of these scholars was undoubtedly Jean-Baptiste Jollois, one of the archaeologists who had accompanied Napoleon's Egyptian expedition. Closer to home, as a civil engineer for the city of Paris, Jollois reported the discovery of Roman roads and graves discovered during earthworks. More importantly, he published studies accompanied by interesting engravings of the aqueduct and the Cluny baths.

The birth of Parisian archaeology

The work of Théodore Vacquer (1824-1899) heralded the real birth of Parisian archaeology. An architect with a colourful personality, Vacquer held various positions in the Paris administration overseeing archaeological sites until he was appointed curator at the Carnavalet Museum, where he created the archaeological section. It is to Vacquer that we owe the rediscovery of most of ancient Paris-including its monuments and its road system, unearthed during Haussmann's great urban reconstruction program. Before Vacquer, the layout of Lutetia had only been based on ancient accounts, and every new discovery forced scholars to make these sources correspond to the finds, with mixed results. Unfortunately, Vacquer's work was left in the form of notes. Finally, in 1912 Félix-Georges De Pachtere took this precious archive and incorporated it into his book Paris à l'époque gallo-romaine. For the first time, an overall view of the birth of the city was available. Paul-Marie Duval took up from De Pachtere, concentrating on the city's monumental structures. He published the second major contribution to the understanding of the city's origins, Paris antique, which appeared in 1961.