- Home

- The town and the abbey

- The medieval town

- Saint-Denis prospers 13th-mid-14th century

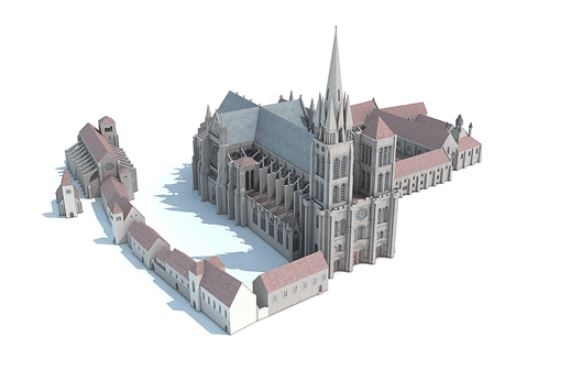

Layout of the monumental complex, 13th century.

© Ministère de la culture / M. Wyss ; A.-B. Pimpaud ; M.-O. Agnes.

Reconstructed view of the monumental ensemble, 13th century.

© Ministère de la culture / M. Wyss ; A.-B. Pimpaud ; M.-O. Agnes.s.

Completion of the architectural program

Suger's abbey-church demained unfinished, and we may imagine that the old Carolingian nave, by then four centuries old, had begun to fall into ruin. Thus, in 1231 the abbot Eudes Clément du Mez embarked on its reconstruction, the most spectacular part of which was the creation of the two transept rose windows. The works benefited from the presence of the renowned architect Pierre de Montreuil, and involved modifying most of the royal tombs. In 1264, the bodies of the kings and queens were regrouped beneath the transept crossing. The "Commande de Saint Louis" featured sixteen gisants that displayed, in symbolic fashion, the dynastic continuity of eight Carolingian rulers followed by eight Capetians. This was the beginning of the famous "cemetery of kings". The church was completed in 1281. In the monastery, this period of opulence was reflected in the reconstruction of most of the claustral buildings. At the same time, the architectural framework of the abbey's large cemetery reached its limits with the construction of the Sainte-Geneviève, Saint-Michel-du-Charnier and Madeleine churches. It was only in 1242 that Saint-Jacques-a church located to the south of the abbey, and reserved for the monks' servants-was mentioned for the first time.

Urban dynamics

As its settlement became denser, the monastic borough took precedence over other surrounding built-up areas. The urban extension overflowed the boundary wall, whose moats became progressively silted up. Nevertheless, the Croult, -the canal that supplied them with water-was preserved, contained within carefully maintained stockade-type walls. This river was a driving force in the economic life of the town. Over time, its banks became home to a series of workshops; in particular, the quality of the water favored the development of drapery and tannery activities. In 1229, the abbey built a second hall which forced it to transfer the town's original jail to the Porte Compoise, which became the châtelet.

The outskirts

The town continued to grow, both at the gates of the castellum and along the four roads leading to it. Saint-Denis linked up with the built-up areas of Saint-Marcel, l'Estrée and Saint-Remi. We know the most about the "terre de Saint-Marcel", because it there is an archive that contains a number of documents relating to the never-ending disputes between the abbey and the lords of Montmorency. The legal decisions, which mostly concern the public roads, testify to the intense trade that must have benefited the development of this inner suburb. The Sainte-Croix church, mentioned in 1205, was probably the result of the break-up of the Saint-Marcel parish. We do not know the exact location of the Saint-Nicolas-des-Aulnes church, which probably stood between the Seine and l'Estrée.

In 1294, the lords of Montmorency gave the village of Saint-Marcel to the abbey, and henceforth the religious orders were the sole masters of the town and its territory. Despite the Black Death-a plague that struck in 1348-the fourteenth century was a great period of prosperity for the town, whose expansion went hand-in-hand with the growth of its activities. The Lendit Fair reached its apex in the years between 1300 and 1360. In the town, construction continued unabated and the use of freestone spread to secular architecture. In the vicinity of the monumental ensemble, several vaulted cellars were built. In 1328, Saint-Denis contained 2,351 hearths or nearly 10,000 inhabitants. During this same period, the population of Paris was almost 200,000.