- Home

- The town and the abbey

- The town within its walls

- The town in troubled times (mid-14th to 16th century)

The town protects itself

At the start of the Hundred Years' War, the abbey was concerned with protecting itself. The abbey's chronicles tell us that, in 1347, Saint-Denis began "to create defensive ditches in the vicinity of the town". The ditch discovered during an archaeological dig in the Saint-Remi quarter probably dates from this period. Starting in 1356, the abbot and the regent Charles-the future Charles V-joined forces to build a city wall. Ten years later, however, the town was still not defensible. The king thus ordered the outlying suburb of Saint-Remi to be demolished. The town retrenched behind a smaller perimeter wall. It surrounded the monastic town, Saint-Marcel and the Estrée neighborhood, but left out Saint-Nicolas-des-Aulnes, Saint-Remi and the major portion of the abbey's orchard, La Couture, which was surrounded only by a simple wall. The town's new wall featured five gate-towers, providing access to the principal roads.

Reconstituted view of the monumental complex, late 16th century. Based on Sylvain Le Stum and Béatrice Jullien works.

© Ministère de la culture / M. Wyss ; A.-B. Pimpaud ; M.-O. Agnes.

The disasters of the Hundred Years' War

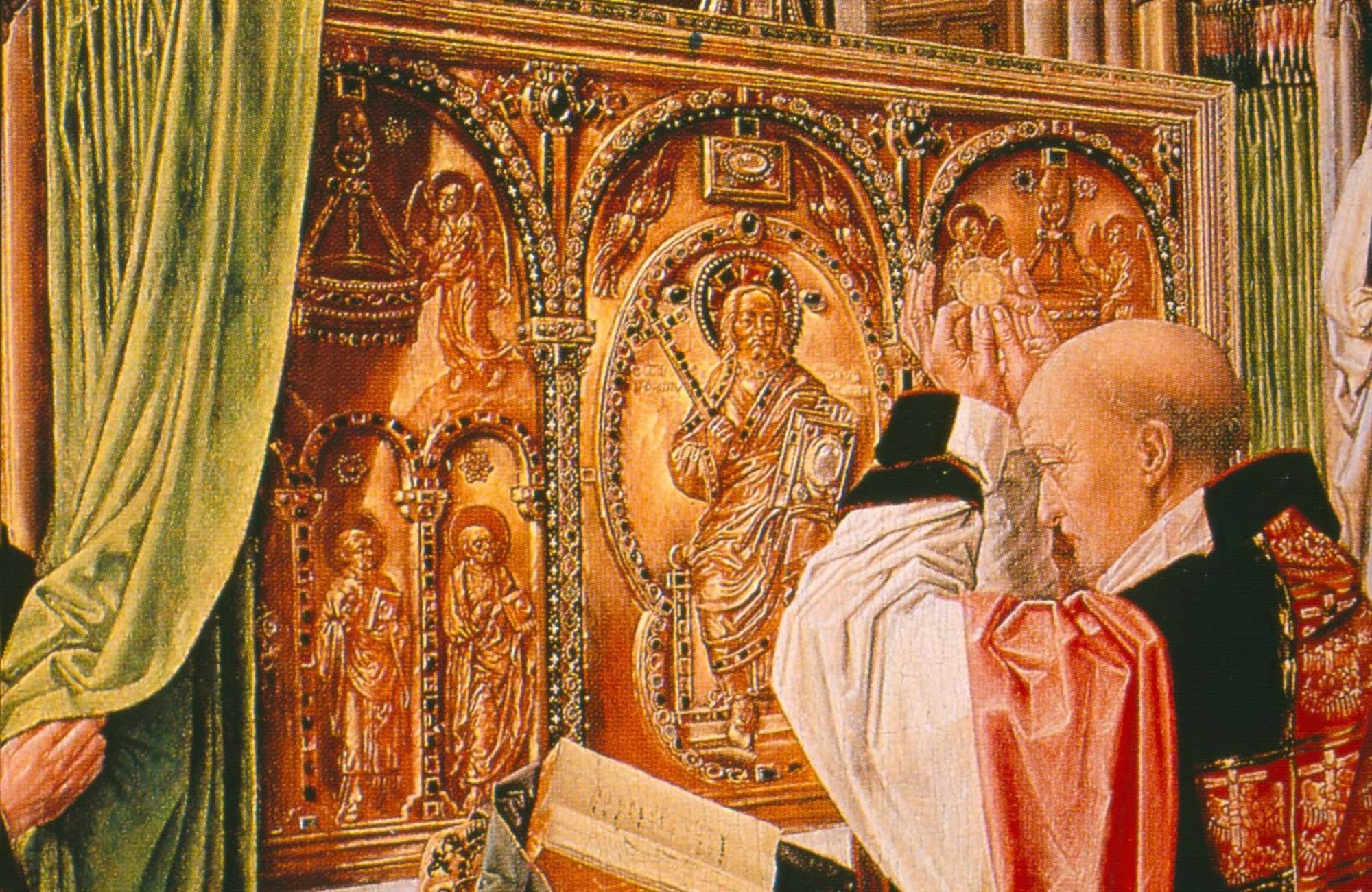

From 1410 to 1436, the town suffered successive attacks by the Burgundians, the Armagnacs and the English. In wartime, Saint-Denis was a strategic site. Its control of the roads north of Paris meant that its occupants could deprive the capital of supplies by cutting off its access to the fertile fields of the Pays de France. The abbey itself was a site worth occupying, as it held the relics of the country's patron saint, the guarantor of the kingdom, and maintained an ancient and privileged connection with France's royalty. In addition, the abbey's treasury-one of the richest in the medieval West-was an object of envy, as it could be used to finance wars. Progressively, the various invading armies transformed the abbey complex into a citadel. In 1435, the town was recaptured from the English by Dunois, the Bastard of Orleans. The wall was partially dismantled and the town's inhabitants fled, seeking refuge in Paris.

Urban development stagnates

During this period of upheaval, practically the only architectural work carried out was on the town's religious buildings. The Saint-Marcel church was enlarged and given an ossuary-crypt. Secular construction, on the other hand, stagnated. The abandonment of a part of the housing meant that small parcels of land could be consolidated. A continuous frontage of small houses is maintained only in the town's squares and market streets. In economic terms, the town entered a difficult period. At the same time, the abbey's revenues were strained by the decline in the Lendit Fair, which would start up again in 1444.

Signs of economic recovery

In 1529, François I appointed the cardinal Louis de Bourbon as abbot commendataire to the abbey. The cardinal was a member of the royal family, and he was the first in a series of nine abbots, who were lay or secular ecclesiastics. To reconnect with the splendour of the abbots of the fourteenth century, in 1530 the cardinal ordered work to begin on a sumptuous dwelling. Around 1572, Catherine de Medicis began work on the Valois mausoleum, located to the north of the abbey-church. Local artisans benefited from this upturn in construction: the abbey's account books mention the merchants and craftspersons who took part in these projects and who, for the most part, lived in Saint-Denis.

Fresh troubles

In 1567, Saint-Denis was once again disrupted by the Hugenot occupation. The monks, taking the treasury with them, sought refuge in Paris, abandoning the monastery to the heretics who caused a great deal of damage and laid waste to most of the churches of the monumental complex. The Saint-Paul church was practically destroyed, forcing the canons to withdraw to a portion of its side aisle that was set up as a chapel dedicated to Saint-Pantaleon. In the same way, the Sainte-Geneviève, Saint-Michel-du-Degré and Saint-Barthélemy churches were damaged. The seats of the three parishes were therefore united in a single building, partially reconstructed, which archaeology has shown possessed a single choir with three small apses. Records state that the three clerics were required to live "peacefully together until two of them being dead, their titles would be eliminated and the last survivor would remain the sole cleric". The choir, which probably held three altars, is the manifestation of this provisional arrangement.