- Home

- Megalithism in Morbihan

- Le Petit-Mont

- From the Campaniforms to the Gallo-Roman era

Although the shallowness of the soil at Petit-Mont has prevented the preservation of any pre-megalithic structures, apart from the mound under cairn I, there is substantial evidence of occupation of the site at several later periods.

From the Chalcolithic Age to the Bronze Age

- A small gold-leaf plate with holes allowing it to be stapled or sewn onto a fabric or onto leather, is a decoration often associated with bell-beaker ceramics (several sherds of which were found in the entrance to dolmen IIIa).

- A large heart-shaped dolerite axe-hammer found during the excavations of 1865 may date back to the same transitional period, between the Neolithic and the Bronze Ages, around the end of the 3rd millennium BC.

- Pottery sherds with relief decorations showing finger- and nail prints could mean that the site was used, albeit infrequently in the Middle or Late Bronze Ages.

The axe-hammer of Petit-Mont (length 223mm).

From the Iron Age to the Roman Era

- Remains dating from the second Iron Age are much more extensive: several beads and glass ring fragments, several billon stater quarters (two of them can be identified as belonging to the Vénètes) and a series of ceramic sherds (including the fragments of a beautiful carinated bowl).

- Like many south Armorican megalithic sites, Petit-Mont was in some way "reappropriated" during the Roman Era, and the dolmen III entrance was transformed into a small sanctuary.

A lot of common ceramic sherds, several fragments of terra sigillita pottery and many remains of white clay Venus statuettes (some attributable to the Rextugenos workshop, which appears to have been producing them in Ille-et-Vilaine at the end of the first century AD).

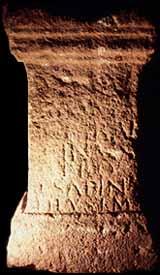

Nevertheless, the main item for this period is a sandstone altar, dedicated to a certain Quintus Sabinus by his son.

Strangely enough, this apparently ordinary name is also that of one of the Roman generals involved in western Gaul during the 56 BC campaign, which ended with the naval defeat of the Vénètes. If not simply a coincidence, it could help to explain why this site, overlooking one of the possible battle locations, later became sacred.

By contrast, only a few medieval and modern age coins have been found there: tenuous signs of sporadic occupation, possibly explained by the presence of a small coastguard shelter nearby.

The altar dedicated to Quintus Sabinus.