- Home

- Trade and navigation

- Trade circuits

The benefits of trading

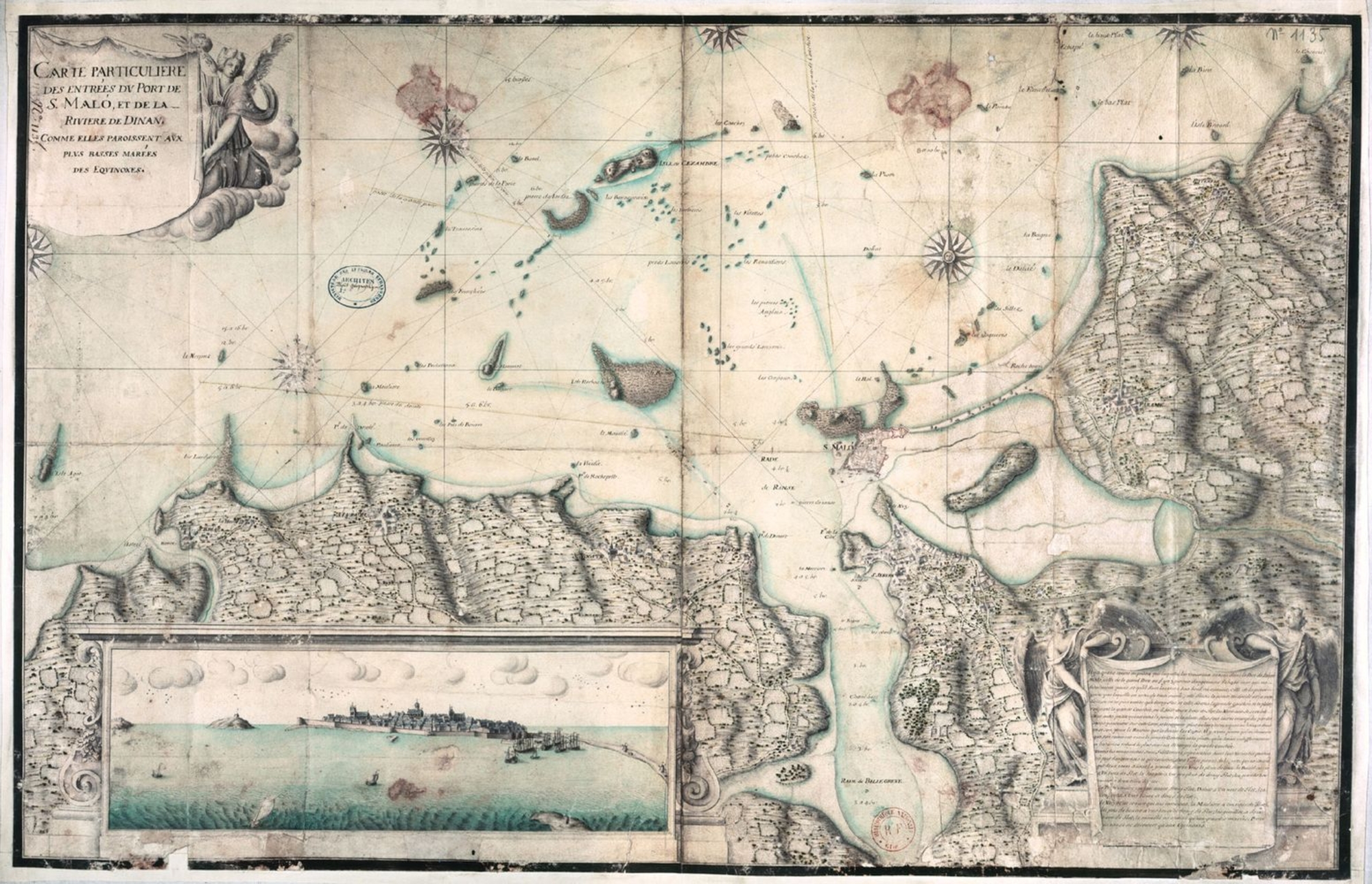

The port of Saint-Malo is a uniquely complex, and even inhospitable, site. And yet, this geography turned out to be an exceptional asset over the centuries, and the city's merchants gradually expanded their activity across the globe in the course of the 17th and 18th centuries. Their ships plied every sea, and it was common for their sons to go off and spend several years in one of their far-off trading posts, particularly in Andalusia, which traded regularly with Saint-Malo.

Closed in behind its walls, the city did not – in contrast to the rival Brittany city of Nantes – have manufacturing capacities, whose products could justify the growth of its port activities. However, the rapid expansion of shipyards building both trade and fishing vessels, combined with a market for goods that itself justified considerable import activity (food, construction materials, wood, etc.), contributed to urban democracy. This trading involved hundreds of ships, many from ports in Brittany and Normandy, but some from much farther afield. It was so extensive that André Lespagnol, a specialist on Saint-Malo trading from this period, has estimated that its share of overall port trade increased from 15 to 25% between 1680 and 1725.