- Home

- Trade and navigation

- Trade circuits

- The port's ability to adapt

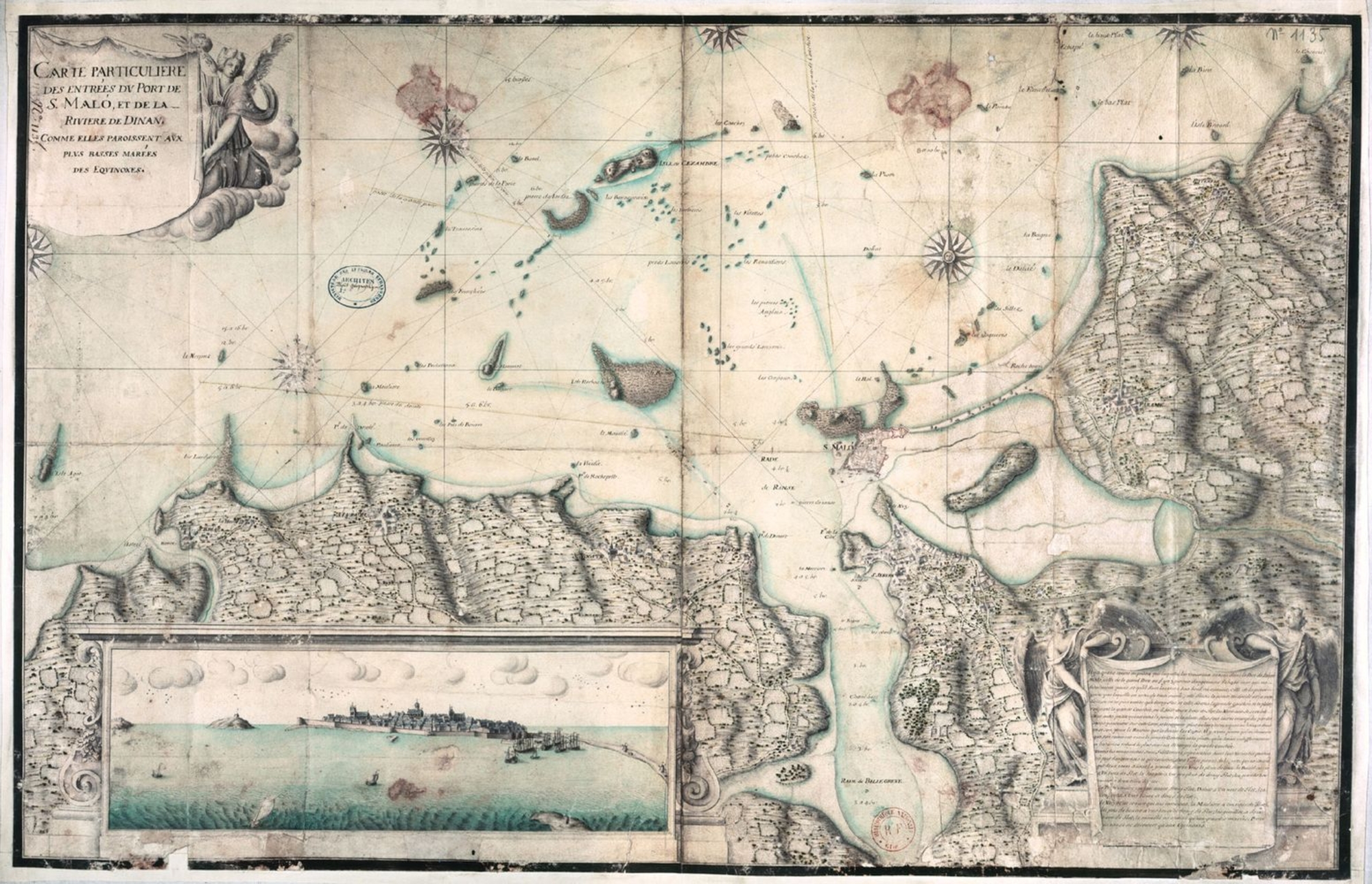

Until the 1670s, Saint-Malo benefited from being a port franc, a privilege granted to Brittany ports since the reign of Charles VI, and it grew accordingly. The construction of fishing vessels, which had developed in the early 16th century, was the backbone of the city's trade, even though dried cod was not popular in the markets of western and northwest Europe. This lack of interest meant that ships were obliged to return via southern Europe. Unfazed, the Saint-Malo merchants took advantage of these Mediterranean excursions and established themselves in the shipping trade that supplied the intra-European trade routes. At the same time, they did not waver when other trade circuits opened up starting in the 1670s, such as that of the Antilles (which was off-limits to them), forcing them to bring their cargoes directly back to Saint-Malo. Wartime privateering, the discovery of the South Seas route via Cape Horn, trade with China via India or the Pacific, and the coffee trade were merely logical extensions of the Saint-Malo merchants' amazing ability to adapt. This trading elite had, in the 17th and 18th centuries, put Saint-Malo at the very top of the list of French trading ports.