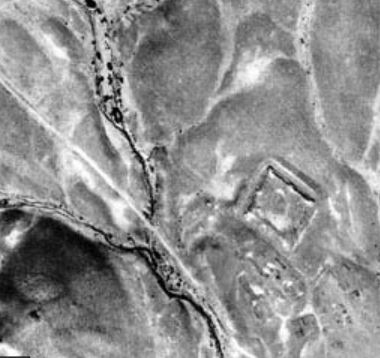

Aerial view of the Roman presence in the arid zones of North Africa. Photo-interpretation: Baradez.

Aerial view of the Roman presence in the arid zones of North Africa. Photo-interpretation: Baradez.

Systematic prospecting started in America in 1929, thanks to a pilot whose 1927 transatlantic flight had made history — Charles A. Lindbergh. He achieved particularly good results flying over tropical and equatorial zones in search of Mayan sites. Starting in 1948, enormous figures of animals, straight lines, and geometric figures were discovered on the arid plateaus near the city of Nazca, in the foothills of the Andes. These figures date from 200 BCE to 600 CE.

Léo Deuel (1969) has written a good history of aerial research on both sides of the Atlantic. Starting in the early twentieth century in Europe, with the help of a balloon, aerial photographs were taken of monuments such as Stonehenge in Great Britain, or Rome and Ostia in Italy. During the First World War, aerial photography was

systematically used to direct troop operations on the ground, as well as aviation. It was mostly in the desert and sub-desert regions at the edges of the eastern Mediterranean that members of the English, German and French military very quickly obtained positive results in detecting ancient ruins from the air. Extraordinary photographs were taken between 1925 and 1942 in Syria by Father Poidebard (1934)), who studied the Roman limes, the city of Tyr and its underwater port, and the Byzantine limes of Chalcis. His photographs, which were published in "L'Illustration", made him famous, despite the ironic comments of certain scholars who at first considered him "an eccentric à la Jules Verne"!

After the Second World War, another Frenchman, colonel J. Baradez (1949) published an important volume of aerial photographs taken by the army in raking light. Baradez condemned photographs taken at an angle, and recommended the exclusive use of aerial surveys. He once remarked, "there's no salvation outside the stereoscope"!