- Home

- Mosul Cultural Museum Collections and Legendary Sites

- A Major Empire

Following directly the Middle-Assyrian kings of the 2nd millennium BC, the Neo-Assyrian rulers developed a military strategy, initially defensive but becoming more clearly offensive. This led to the formation of an immense empire stretching from the Levant to the Iranian plateau and from southern Anatolia to the shores of the Gulf.

The development of Assyrian power

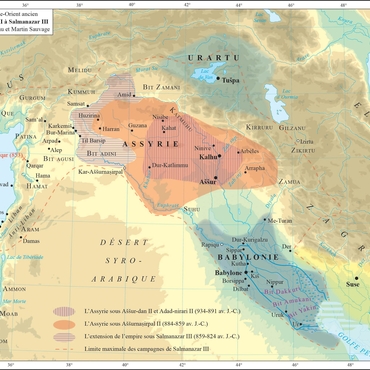

Without access to the sea and exposed to attack by their neighbours, particularly the Arameans, the Assyrian rulers defended the area around the capital Ashur, at the heart of their kingdom, until the 10th century to guarantee the safety of their communication routes. From the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) on, the Middle-Assyrian kings went much more on the offensive. Setting out to reconquer lost territories to the east and west of the land of Ashur, they conducted military campaigns whose violence inspired terror.

An immense empire

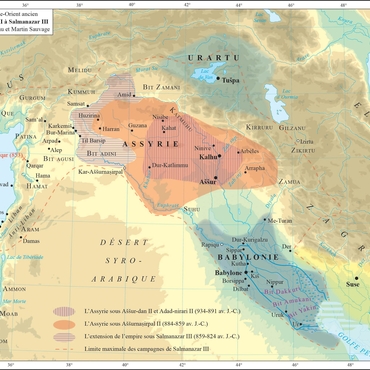

The son of Ashurnasirpal II, Salmanazar III (859–824 BC) continued the conquests, but his successors were weakened by internal problems. After what is sometimes referred to as a "growth crisis," the real birth of the Assyrian Empire came with the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC). A period of prosperity followed as the empire grew under the reigns of Sargon II (721–705 BC), Sennacherib (705–681 BC), Assarhaddon (680–669 BC) and finally Ashurbanipal (668–626 BC). Although he is said to have inspired the distorted legend of Sardanapalus, Ashurbanipal is considered the last great king before the fall of the empire in 610 BC, in the face of a joint attack by the Babylonians from Southern Mesopotamia and the Medes from Iran, led by Nabopolassar and Cyaxare.

Enriched by the spoils and tributes taken from the conquered populations, some of whom were deported from their places of origin to strengthen its power, the Assyrian Empire forged a reputation of terrifying excess. This reputation was relayed in large part by the Bible and Greek authors. The military successes of the Assyrian monarchs allowed them to undertake major building projects in three successive capitals of the empire: Kalhu (now Nimrud), Dur-Sharrukin (now Khorsabad) and finally the famous Nineveh, from where several major works of art were exhibited in the Mosul Cultural Museum in the Assyrian Hall.

The archaeological rediscovery of the Assyrians

In 1842, Paul-Émile Botta, who had just been appointed French consul in Mosul, began the first archaeological excavations in the orient. Having first briefly explored ancient Nineveh, Botta finally excavated the site of Khorsabad. The British began excavating in Nineveh shortly afterwards.

The sensational results of these early excavations were first presented to the public in 1847 in Paris at the Musée du Louvre, where the world's first Assyrian Museum was opened. This was the beginning of the archaeological rediscovery of the Assyrian world, whose writing was soon deciphered. Less than two hundred years later, excavations and research have made it possible to recover the forgotten memory of Mesopotamia’s long past — of which the Mosul Cultural Museum preserved several remarkable works of art.

Associated media

Open Media Library

Map of the Assyrian Empire (8th and 7th centuries)

Paul -Émile Botta (1802–1870)

The Death of Sardanapalus, by Eugène Delacroix, 1827

The Great Hall of the Assyrian Museum in the Louvre in 1862

Victor Place and Félix Thomas at the Khorsabad site, around 1852