The Cro-Magnon rock shelter

At the end of March 1868, the human remains of several individuals were discovered in the Cro-Magnon rock shelter during work on a railway line near Eyzies (Dordogne). People were already aware of the existence of the Neanderthals, but this was the first discovery of anatomically modern humans dating to the Prehistoric period. The antiquity of Prehistoric humans and their ingenuity had been revealed less than a decade before, but their physiognomy was still unknown.

For 150 years, the human remains have been subjected to multiple studies into populations, pathologies, burial practices, and the like. Shells used as burial decoration gave a date of between 32,000 and 31,000 years ago.

The discoveries made in Cro-Magnon marked a milestone in global Prehistory studies and in defining our species: anatomically modern humans or Homo sapiens.

Excavation and discovery of the site

The chance discovery of the Cro-Magnon fossils, at a time of growing interest in Prehistory in the region around Les Eyzies-de-Tayac (Dordogne), had an immediate and seismic impact. Designated by the Ministry of Public Education, Louis Lartet, son of Édouard Lartet, evaluated the discovery and led the excavations. He made an official presentation on the discovery on 16 April 1868 in Paris.

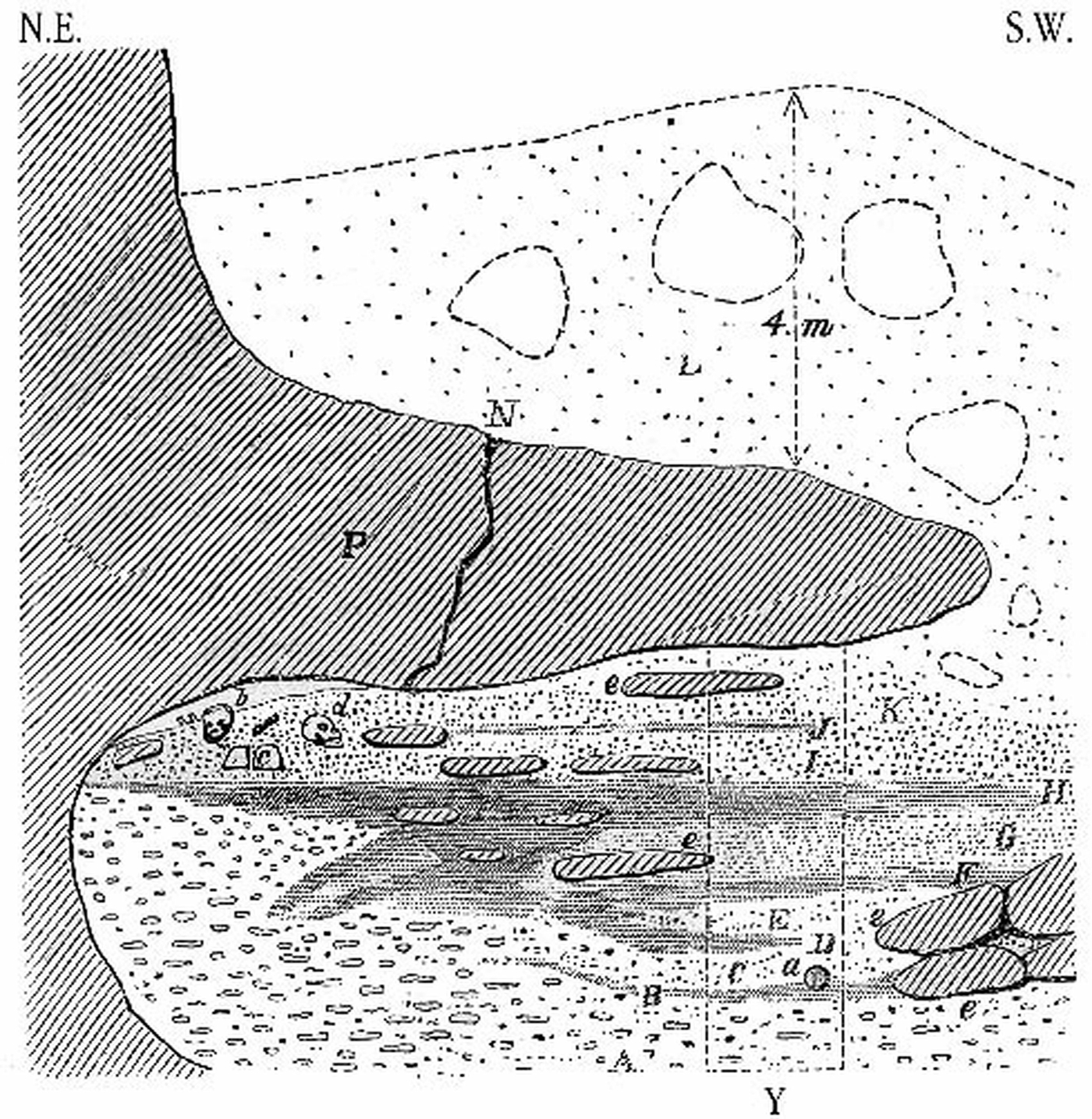

For Louis Lartet, the size of the mound covering the shelter and the association of human remains with fauna dating from the Quaternary proved the antiquity of the burial site. However, many questions remain unanswered due to the age of its excavation and the chance nature of the discovery. The excavation led by Louis Lartet was limited in time and scale and focused on the lower section of the fill. The shelter was then emptied of its contents.

The newspaper articles and multiple scientific publications that appeared after its discovery document the impact of the event. Anthropologists were finally able to study almost complete skeletons whose anatomical features were identical to our own: "Cro-Magnon man" became the chief representative of our Prehistoric ancestors.

"It seems, then, that fossilised man, Antediluvian man, Prehistoric man, really did exist, and soon it will no longer be possible to doubt this considerable fact, about which science has all the information it needs to provide us with a definitive answer," Eugène Massoubre, 1868. Local column. L’Écho de la Dordogne. 10 April 1868

Defining Modern Man

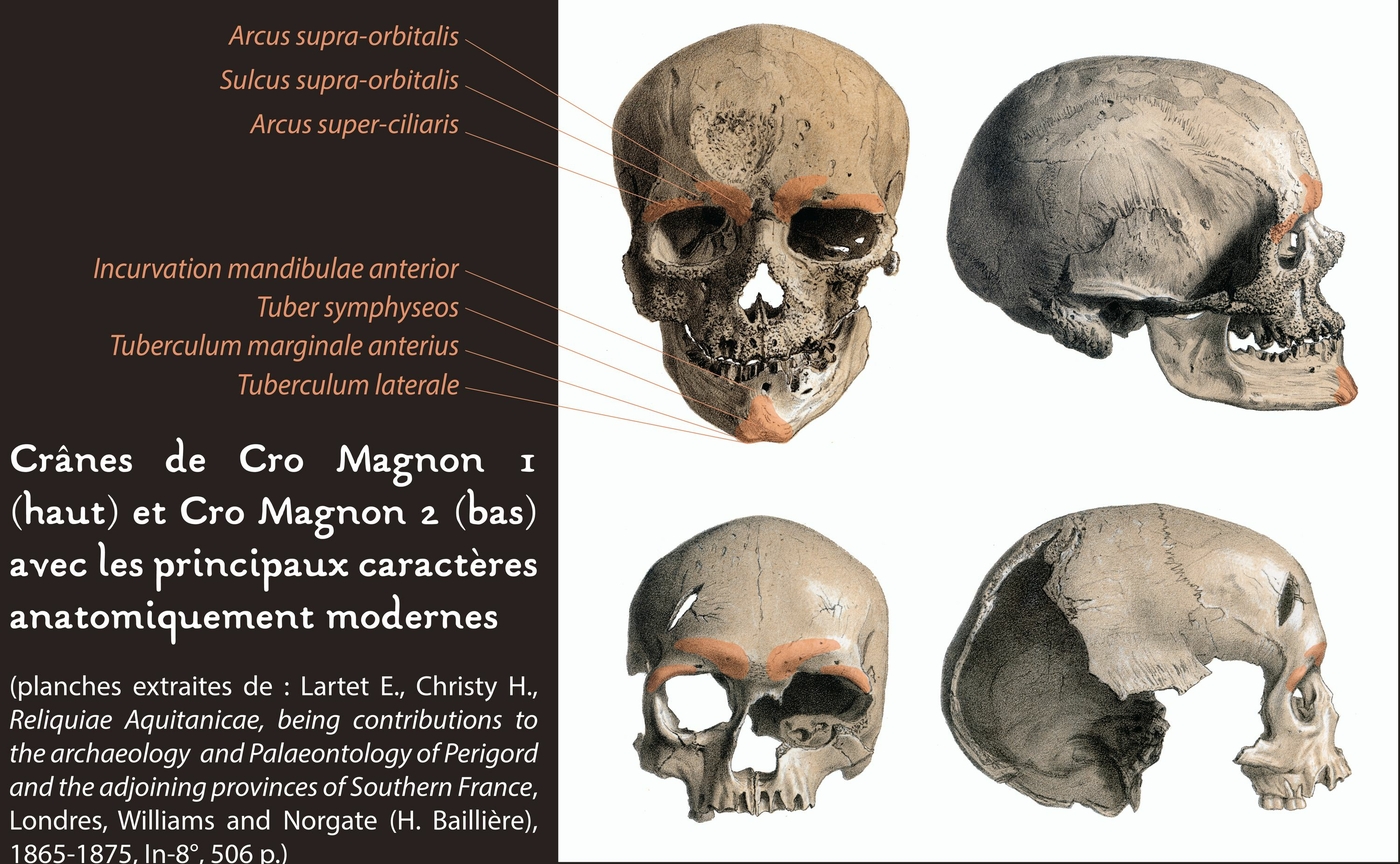

The defining criteria for anatomical modernity are primarily related to the skull, particularly the superciliary ridges and chin. Although everyone has heard of “Cro-Magnon man", scientists now prefer to use the term “anatomically modern man" for the sake of accuracy. It is a member of the Homo sapiens species, the oldest representatives of which have been found in Africa and the Near East. Given the current state of our knowledge, the origin of Homo sapiens is much more difficult to determine and there is no consensus within the paleoanthropological community on how to define this species.

The rock shelter: habitat and then grave

When it was first discovered, the layers in which the remains were found were dated to the Aurignacian, defined a few years earlier by Édouard Lartet (1861). Despite objections relating to the association of the human bones with the archaeological layers, the development of new subdivisions for the Upper Palaeolithic (particularly the Aurignacian, divided in 1912 by Breuil into Châtelperronian, Aurignacian and Gravettian) and many other proposals, not always grounded in evidence nor without ulterior motives, the burials were mostly considered to date from the Aurignacian.

Unfortunately, it is now only by studying collections held by different institutions that we can, a posteriori, consider the shelter to have also contained, in addition to a major Aurignacian sequence, subsequent traces of occupation or passage during the Gravettian and Solutrean periods. However, according to the stratigraphy recorded by Louis Lartet, the human fossils were found at the base of the upper section of the fill. After several (14) failed attempts at radiocarbon dating the human remains, one of the 300 ornamental shells of the Littorina littorea species (Atlantic shellfish) associated with the burial was dated to the Early Gravettian.

The Cro-Magnon rock shelter was therefore an Aurignacian habitat, and then, when it was almost full, a Gravettian burial.

Aurignacian habitat

The Aurignacian saw the emergence of Homo sapiens in Europe and the advent of cultural modernity, including remarkable symbolic expressions ‒ ornaments and art ‒ of innovative know-how and evidence of the adoption of complex social rules.

The most recognisable archaeological remains in the Cro-Magnon rock shelter belong to the Early Aurignacian. Strong blades knapped from wide cores were retouched at the tip as scrapers or along their length as Aurignacian blades, sometimes “strangled" (concave edges). The blades were produced instead of the carinated fronts of thick scrapers. Lastly, hard animal-origin materials were used to make a wide range of objects including spear tips, punches and burnishers.

Burial site

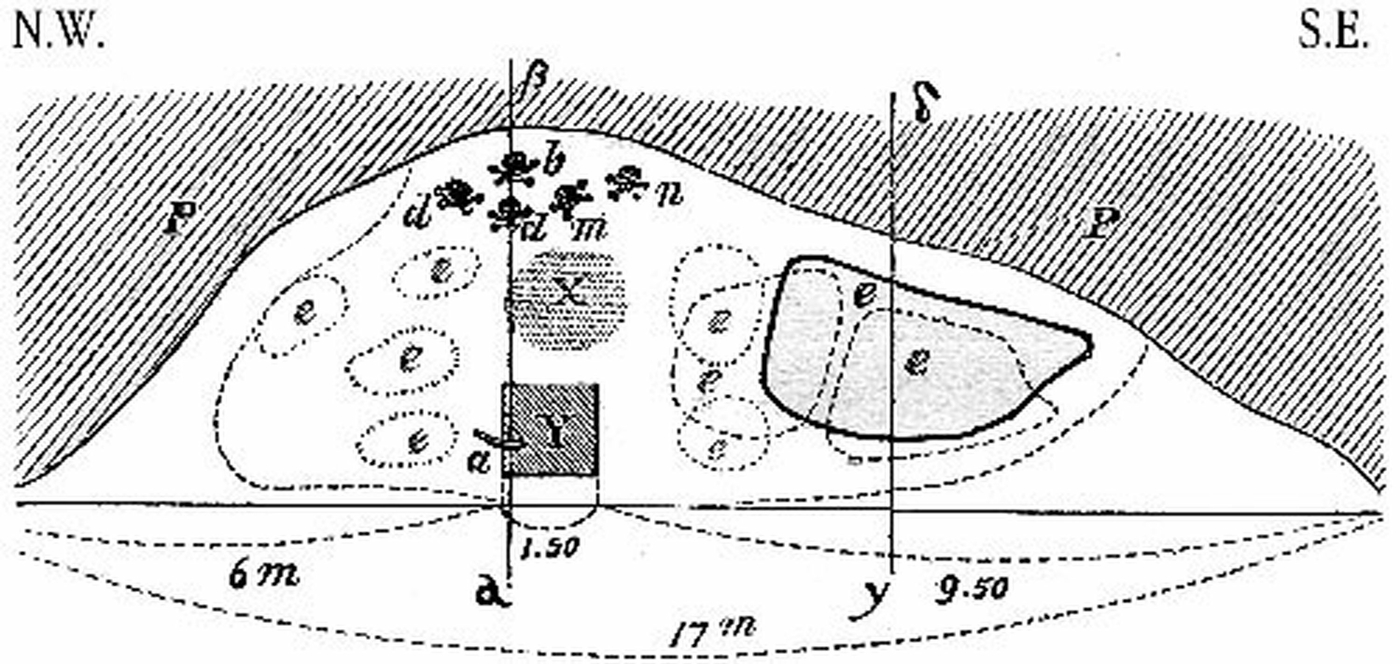

Although no burial pits or burial structures were observed, and no evidence of the position in which bodies were buried has survived, the section and compact plan of the bone distribution suggest the deceased were grouped in a restricted area, in the upper section of the fill, at the back of the rock shelter and very close to the ceiling. This location cannot be explained by a natural phenomenon.

The deposit is therefore intentional; small bones suggest we are looking at a primary deposit. Red ochre, periwinkle shell adornments and ivory pendants found close to the bones are suggestive of body decoration burial practices or perhaps the use of grave goods. The bones are still heavily stained with ochre. The periwinkle shells, large in number, are found in museum collections across the world. Archaeologists do not know, however, how these adornments were worn or if the ochre was used by the living or exclusively for the dead.

Bones

The Cro-Magnon rock shelter contained more than 120 human bones. Since we do not know their primary position, it is very hard to group them by individual. Archaeologists are using virtual reconstruction and other techniques to support their research. Skull fragments suggest at least four adults were buried in the cave. Extremely fragmentary remains document the presence of at least three neonates and one older infant. The most complete skulls belong to two adults, one probably male (CM1, dubbed “the old man"), the other, more slender, perhaps female (CM2). Both are relatively old but, since no teeth were found, we do not know their exact age. The frontal bone lesion of CM1 is now thought to have been caused by disease, although which disease is the subject of heated debate. Although various diagnoses have been proposed, this disease is probably not the cause of death. The adult CM3, of which only the skullcap remains, may also be male. Archaeologists also found hip bones, only one of which can be matched with a skull (CM1), of two men and one woman, all over the age of 40. The lower limbs, recently matched, suggest they were fairly tall ‒ 1.7 to 1.77 metres for the men and approximately 1.65 metres for the woman ‒ and sturdy. Since there is no collagen to carry out DNA analyses, however, it is impossible to demonstrate kinship between the individuals.

Several people are buried in the Cro-Magnon rock shelter but it is not possible to determine if the dead were deposited at the same time. Concretions on the bones of the “old man" suggest this individual at least did not receive a “proper" burial, that is, they were not covered with sediment. Leaving bodies in the open-air appears to have been characteristic of the South West of France during the Gravettian.

The Gravettians

The humans found in the Cro-Magnon rock shelter were sturdier than humans today. The strength of their lower limbs and of the other subjects dated to the Gravettian is probably due to a significant level of mobility. The upper limbs of the male individuals displayed a marked asymmetry, which was found to a much lesser degree in the females; this has been interpreted as due to a specific division of labour between men and women, the nature of which remains to be determined.

The Cro-Magnon rock shelter has welcomed visitors since 2014. Research continues, some 150 years after the discovery of the first Cro-Magnon fossil, and Prehistory continues to reveal its secrets.

The Cro-Magnon rock shelter in museum collections

-

Anthropological remains are conserved and displayed in the Musée de l’Homme.

-

Archaeological remains are conserved in several museums; some are displayed in the Musée d’Archéologie nationale, the Musée national de Préhistoire des Eyzies, thanks to a loan by the Museum d’Histoire naturelle de Toulouse and in the Musée d’art et d’archéologie de Périgueux.

Did you know?

- The name Cro-Magnon is a French adaptation of the Occitan Cròs-Manhon [krɔ.ma.ˈŋu] Cro means “hole, hollow, cave" and Magnon might signify “Large Man" or be the name of a person.

Useful information

- Prepare for your visit: www.abri-cromagnon.com

- Musée de l'Homme: www.museedelhomme.fr/en

Bibliography

- Lartet Edouard, Christy Henri 1865-1875 - Reliquiae aquitanicae, being contributions to the archaeology and Palaeontology of Perigord and the adjoining provinces of Southern France, Londres, Williams and Norgate (H. Baillière), 1865-1875, In-8°, 506 p. (chapters VI p. 62-72, IX p. 97-122 and X p. 123-125)

- Broca Paul 1868 - Sur les crânes et ossements des Eyzies. Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris, II° Série. Tome 3,. p. 350-392. URL: www.persee.fr/doc/bmsap_0301-8644_1868_num_3_1_9548

- Henry-Gambier Dominique 2002 - Les fossiles de Cro-Magnon (Les Eyzies-de-Tayac, Dordogne), Bulletins et mémoires de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris [Online], 14 (12), p. 89-112. URL: bmsap.revues.org/459

- Henry-Gambier Dominique 2008 - Comportement des populations d’Europe au Gravettien : pratiques funéraires et interprétations. PALEO, 20, p. 399-438. URL: paleo.revues.org/1632

- Villotte S., Balzeau A., 2018. - Que reste-t-il des Hommes de Cro-Magnon 150 ans après leur découverte ?, Bulletins et mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris, 30 (3-4), p. 146-152.

Research project

- Projet ANR Gravett'Os (resp. S. Villotte) "Biologie, pathologie et comportements des Gravettiens : du squelette aux interprétations palethnologiques" (ANR-15-CE33-0004)