The southwest of the Turkana Basin: a cradle for humanities

The emergence of our species in Africa 200,000 years ago is only one of many steps in the long and complex evolutionary process that gave rise to multiple hominin species. The Turkana basin, due to its position in the East African Rift Valley, contains multiple archaeological and palaeontological indicators that shed light on these evolutionary stages.

In Kanyimangin, the Trans-Evol project records a key period in our evolutionary history: the transition between the Early and Middle Pleistocene between 1,250,000 and 750,000 years ago. This period is characterized by serious climate disruption impacting all ecosystems, including the human populations of the time, but for the moment only three human fossils have survived in a reasonable state. The archaeological excavations carried out in Kanyimangin should allow us to flesh out this sample in order to shed more light on these distant cousins of Homo sapiens.

The southwest of the Turkana bassin

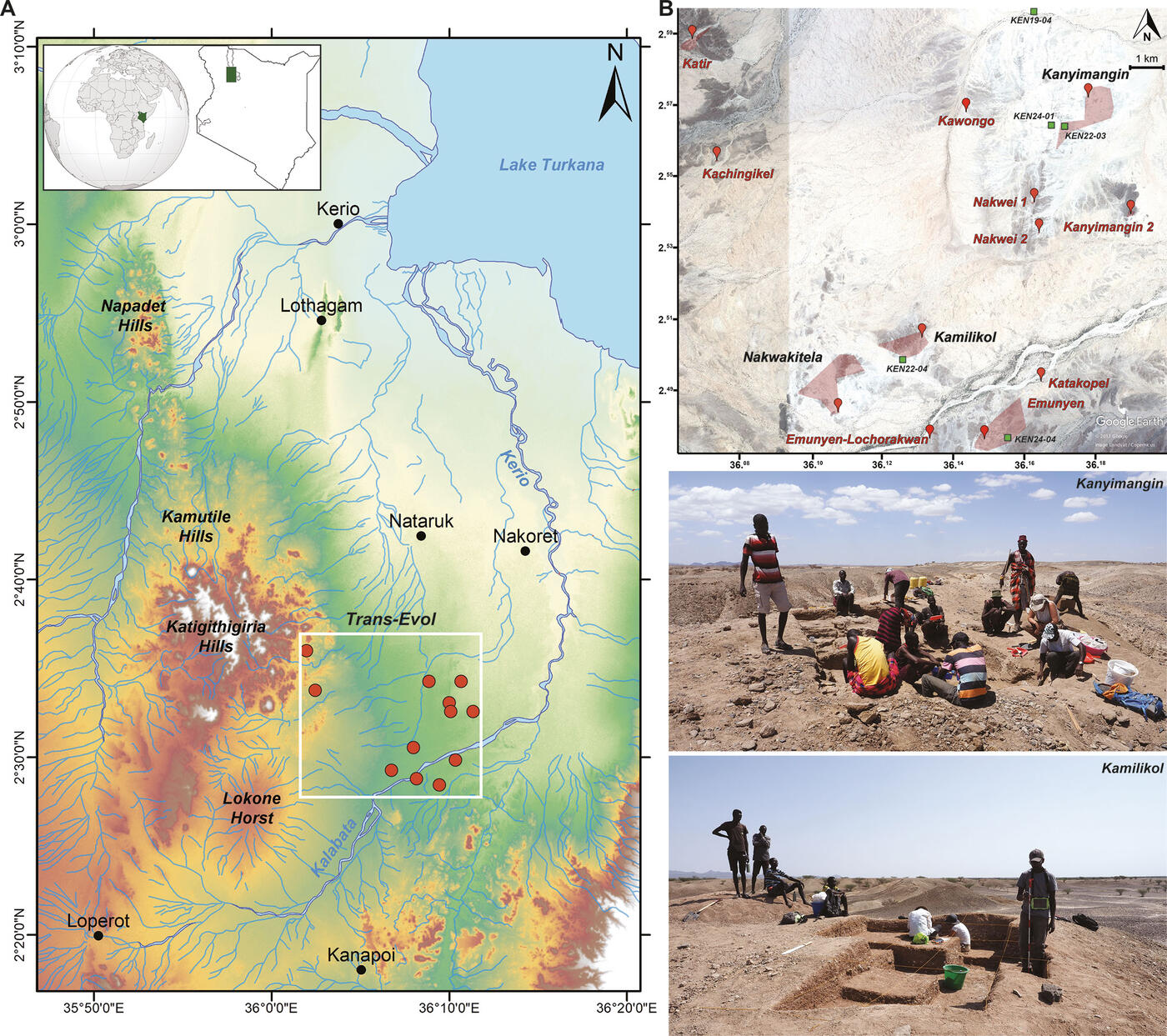

Kanyimangin is located in the southwest of the Turkana Basin, and surrounded by several major archaeological sites. Forty kilometres to the north is Lothagam, a site known for its human occupations dating from the early Holocene, including the celebrated megalith site of Lothagam North. Some thirty kilometres to the southwest stretch the geological formations of the Pliocene site of Kanapoi where the earliest australopithecus fossils were discovered. Lastly, 15 kilometres to the north, is the site of Nataruk where mutilated human remains attest to the earliest known inter-group conflicts in the history of humanity.

Kanyimangin

The main site of the Trans-Evol project was discovered in 2010 by Robert Moru (National Museums of Kenya). This discovery was not immediately followed up with an archaeological investigation and it was only in August 2017 that a survey carried out by Marta Mirazón Lahr, Robert Foley, Frances Rivera from Cambridge University, Justus Erus Edung of the National Museums of Kenya, James Lokoruka from the Turkana Bains Institute and Aurélien Mounier of the CNRS revealed the archaeological potential of the site. Since then, two short excavation campaigns were carried out in 2018 and 2019 led by Aurélien Mounier and a full excavation was scheduled for 2021. The previous campaigns shed light on faunal remains and lithic artefacts, the preliminary analysis of which indicates one or more human occupations of the site. The characteristics of these discoveries and the geochronological analyses currently underway indicate that these occupations took place between 1,700,000 and 790,000 years ago.

Geochronology

From a geochronological point of view, the sediment samples taken in 2018 for magneto-stratigraphic analyses (i.e. palaeomagnetism) provide valuable additional information on the age of Kanyimangin. Palaeomagnetism is the study of the record of the Earth's magnetic field in the past. The magnetic minerals contained in magmatic and sedimentary rocks are able to fossilise the intensity and directions of the magnetic field at a given time. The direction of the Earth’s magnetic field currently points to the geographic north of our planet, called the magnetozone of normal polarity. This direction is nonetheless not stable over geological time and on many occasions the azimuth of the Earth’s magnetic field indicated the geographic south of the Earth, that is to say, a magnetozone of inverse polarity. The analyses carried out by C. Chapon-Sao (CNRS) on samples from Kanyimangin indicate that the sediments formed in a period when the azimuth of the Earth’s magnetic field indicated the geographic south. This result gave a minimum age for the site of 790,000 years, the start of the current period of normal magnetozone.

Fossil discoveries

The description (J. Marín Hernando, MNHN) of fossils found in Kanyimangin suggests they belonged to a species of fauna that has now disappeared. For example, some 40% of faunal remains discovered on the site belong to the Euthecodon brumpti species (see KY.12983). This crocodile, of which the highly elongated rostrum (the anterior part of the skull) is characteristic of a diet mainly composed of fish, probably disappeared some 1 million years ago (Storrs, 2003). Also, the section of upper jaw KY.12985a represents a young individual of an elephant species (Loxodonta adaurora) that may have disappeared some 500,000 years ago. Lastly, many Suidae fossils have been found on the site, including Molar KY.12984, which may have belonged to the Notochoerus genus known to be present in the Turkana basin until around 1,700,000 years ago. These palaeontological data are consistent with the preliminary geochronological determination of the age of the site.

Archaeological discoveries

The preliminary analysis (S. Sánchez‐Dehesa Galán, Université Paris Nanterre, Università della Sapienza) of the shape of the lithic artefacts (knapped rock tools) discovered in Kanyimangin, suggest they might belong to the Acheulean, a lithic industry characterized by two specific types of tools: biface tools (large tools worked on both sides, see KY.11052) and cleavers (retouched flake tools, see KY.12966).

The Acheulean appeared in Africa 1.75 million years ago, where it was steadily replaced by the Middle Stone Age between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago. Human populations dating from the transition between the Early and Middle Pleistocene used this type of tool in their everyday lives. During the transition between the Lower and Middle Pleistocene, the Acheulean evolved and became more complex with the emergence of new percussion techniques such as the use of wooden clubs to shape bifacial pieces, and spread across Eurasia. Alongside this technological development, significant cultural innovations can be identified in the form of the appearance of new hunting methods, as revealed by indicators of the mastery of sharpening practices by hominins in Olorgesailie in the Rift Valley of Kenya.

These technological developments may be linked to the emergence of a new species of human: Homo heidelbergensis. In fact, representations of the Homo genus have survived in numerous biological changes at this period, including an unprecedented increase in brain size but also profound changes in the face and cranial vault. The extremely small number of human fossils dating to this period means that it is unfortunately not possible to determine precisely the morphology of these populations or what they belong to.

Future research in Kanyimangin

Archaeological excavations were set to resume in autumn 2021 as part of the Trans-Evol project. It will involve the geochronological characterization of the site, improving our understanding of lithic assemblage in Kanyimangin, and completing the description of fossil remains in the hope of discovering those of the humans who occupied this site 1,000,000 years ago.

Project supported by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs on the advice of the Excavation Committee (Commission des fouilles).

Useful links

Partner laboratories:

- HNHP UMR 7194 : https://hnhp.mnhn.fr/fr

- LCHES: http://www.human-evol.cam.ac.uk/

- National Museums of Kenya: https://www.museums.or.ke/

Project website: www.trans-evol.org