Decorated rocks in the Île-de-France

A horse and an aurochs were engraved on sandstone rocks near Fontainebleau at the end of the ice ages. The last hunter-gathers then scored a large number of furrows and cross-hatchings into the rocks. This symbolic terrain is a promising field of research in need of protection.

In the sandstone chaos between Nemours and Rambouillet, motifs from different periods are scattered across more than 2,000 cavities, generally very narrow. A programme to safeguard, highlight and study these engravings focuses in particular on works dating from the end of Prehistory.

Heritage under threat

The first decorated shelters were identified in the 19th century and then mostly at the end of the 20th thanks to the work of a highly active group of volunteers. These small cavities escaped the mass destruction wrought by sandstone quarries from which road cobbles and rubble stone were extracted until the early 20th century. However, many of these surviving shelters are now in tourist forests, which once again poses a threat to them. Their friable walls can crumble at the slightest touch, including when people push into cavities without taking proper precautions, and suffer often unintentional damage caused by everything from graffiti to camp fires.

Archiving, highlighting and studying the shelters

A new research team is now archiving a sample of shelters, including using 3D imagery based on photogrammetry. This provides “digital footprints" that can potentially be used to produce facsmilies or to create immersive virtual reality tours. These safeguarding tools are used as resources for an awareness and prevention programme that aims to turn everyone - particularly local residents - into defenders of this heritage. More and more school children are learning about efforts to preserve and promote the shelters, drawing on current studies by some fifteen scientists.

New observations about rare Palaeolithic engravings

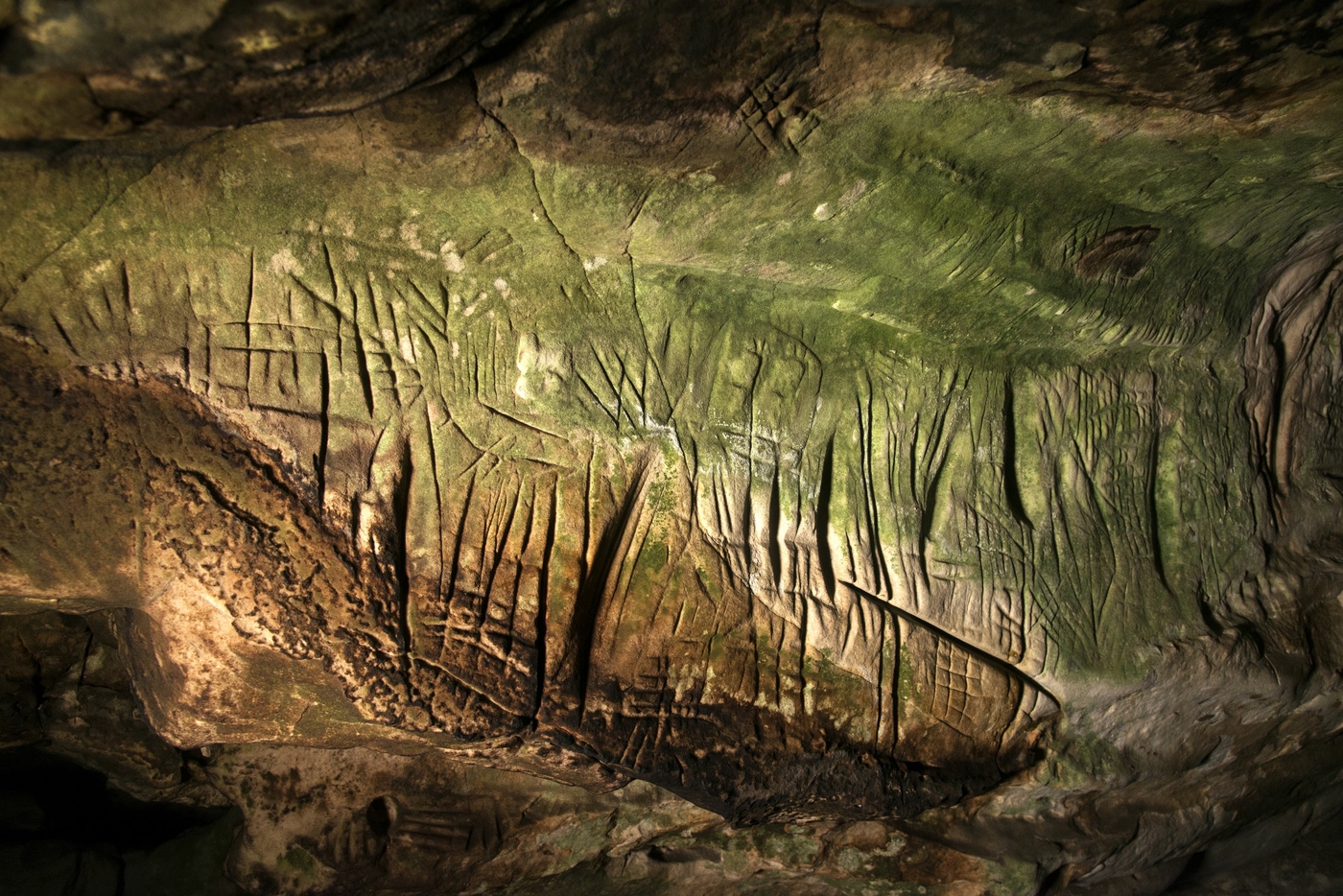

A shelter in Noisy-sur-École (Seine-et-Marne) is finely engraved with a horse, the style of which resembles some of those found in the Lascaux cave (Dordogne). Despite erosion, which has made these extremely old works such a rarity, it is still possible to make out its shape. The horse and another, even fainter horse, surround a natural relief shaped like a female pubis. An in-depth analysis shows that most of the cracks of which it is composed were shaped by humans, and reveals how these modifications eased the occasional flow of water, especially during rainfall. This is not the first time links have been made between rock art from the late Palaeolithic and water flow, but this is the first time a hydraulic system has been found. In another shelter, this time in Buno-Bonnevaux (Essonne), a different style of aurochs and the profile of another animal abutted to it also look as if they were produced in the Palaeolithic period. They are associated with several geometric engravings, possibly more recent, including many wide and deep furrows.

Research into Mesolithic rituals

This deep furrowing, in addition to extensive cross-hatching, are among the main motifs attributed to the Mesolithic period. They are found in a few small cavities that were inhabited during this period and where flint used to engrave the sandstone has been uncovered. In two shelters in Noisy-sur-École, where large numbers of geometric motifs of this kind have been found, archaeologists are attempting to reconstruct the techniques used to engrave them and their sequence. They believe they should be able to establish relations of precedence between the cross-hatching and the deep furrowing that perhaps belong to different symbolic phases. The average time taken to produce the cross-hatching - 10 to 20 minutes for the most common archaeological models - was calculated using experimental reproductions. This is not very long, but still fairly significant, especially if these motifs turn out to have been produced as small series of cross-hatchings semi-parallel to each other, as suggested by other indicators. Moreover, these experiments show that only friable sandstone is suitable for engraving. It is therefore important to include this parameter in large-scale geographic analyses of the distribution of decorated shelters. Their aim is to research, besides the suitability of the rocks for engraving, if there are other criteria - topographic, altitudinal and so on - that led Prehistoric people to select these places for their rituals.

Extremely rare paintings

In Fontainebleau, Seine-et-Marne, an animal painting obscured by recent organic deposits has been partially revealed using image processing analysis. It is now possible to see two cervids, superimposed and head to tail, bearing striking similarities to works on the Iberian peninsula from the late Mesolithic. Likenesses between works, some more than 1,000 kilometres apart, have already been observed in Prehistoric art, but what is surprising in this case is that archaeologists have yet to identity any intermediate stages. This is probably due to erosion and also perhaps to the state of research, which is rapidly gaining ground, as confirmed by these latest discoveries in the south of the Île-de-France.

Useful links

- AFP - A vast Prehistoric site in Fontainebleau, largely unknown in Europe. Report by Grégoire Ozan

Radio programme Carbone 14 / France Culture

Listen to the programme (in French) L’art rupestre à « l’Origine du monde » by Boris Valentin, 14/11/2020

Did you know?

In addition to a handful of sandstone shelters occupied in the Mesolithic period in areas with engravings, archaeological excavations have revealed the remains of habitats of Prehistoric nomadic hunter-gathers, some buried for 500,000 years, in many other parts of the Île-de-France.

Étiolles in Essonne is an example of a well preserved camp from the end of the Late Palaeolithic around 15,000 BCE and rue Henry-Farman in Paris is a site from the Mesolithic dating from around 10,000 BCE.