Christian buildings on the Nineveh Plains

Christianity is traditionally thought to have arrived on the Nineveh Plains, including the city of Bakhdida (Qaraqosh), as early as the end of the 4th century or early 5th century. Former episcopal see of the Syriac Orthodox church, the village became Catholic at the end of the 18th century.

At the heart of the Syriac plains, 30 km to the southeast of Mosul and 80 km to the west of Erbil, Bakhdida is the largest Christian city on the Nineveh Plains. Forty to fifty thousand people lived here before the Daesh offensive. All of the churches were profaned, soiled, pillaged and even set on fire throughout the 26 months of the city’s occupation, from August 2014 to October 2016. Since the liberation, Bakhdida has embodied the promise of renewal on the Nineveh Plains and in Mesopotamia.

Rebuilding on shifting sands in the Nineveh Plains

Since the exodus of the Christians of Mosul, the Nineveh Plains have become one of the last Christian sanctuaries in Mesopotamia. It is both a human and spiritual sanctuary and a major heritage site. Since April 2017, Christians have steadily returned to the towns and villages of the Nineveh Plains. The recovery of Bakhdida (Qaraqosh) has been remarkable, despite the uncertain future facing its inhabitants. International organisations and institutions are supporting their return. Œuvre d’Orient, Fraternité en Irak, Solidarité Orient, Fondation Aliph, Fondation Saint-Irénée, Mesopotamia, Fondation Mérieux and other bodies foster economic and social development while protecting local heritage. This holistic approach is vital. Without heritage there is no community. And there is no community without heritage.

The rebuilding of the Mar Behnam mausoleum, dynamited by Daesh, is remarkable in this respect. French architect Guillaume de Beaurepaire, at the request of the NGO Fraternité en Irak, led the heritage project in partnership with Abdel Salam Alkhodedy, an Iraqi archaeologist from Bakhdida.

The Al-Tāhirā Church in Bakhdida (Qaraqosh)

The Al-Tāhirā Church, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, is the most celebrated Christian building in Bakhdida, with its two churches, the oldest of which is thought to date to the 13th century, while the “new" church was built in the first half of the 20th century. Its proportions are truly impressive. Some 54 metres long and 24 metres wide, the “new" Al-Tāhirā is the largest Syriac-Catholic church in the Middle East. It is a source of pride for the people of Bakhdida, not only for its size but also the sacrifices made by the local population to build the church over a 16-year period, from 1932 to 1948. The inside of the church was once dazzling white before the walls and vault were blackened by soot from the criminal fires start by its Islamist defilers. Daesh also used the courtyard of the church as a centre for weapons training and practice. Since the liberation of the city in October 2016, the Al-Tāhirā church, which is currently undergoing restoration work, has become a leading spiritual and community centre.

The Convent of Mar Behnām and Sārah in Khidhr Ilyas

The Convent of Mar Behnām and Sārah is located in a relatively remote area, 35 km to the southeast of Mosul, in the village of Khidhr Ilyas.

History of a tradition: The church was founded in memory of the martyrdom of Behnām and his sister Sārah, in the second half of the 4th century (372). The pit where they were martyred is a centre of intense popular devotion.

The tradition of Mar Behnām is based on a hagiographic source, probably written in the 12th century: the Deeds of Mar Behnām. It recounts how Sārah, sister of Behnām, was cured of leprosy by the monk Mar Matta, introduced to her by the prince. The scene takes place close to a miraculous spring that, besides curing the skin disease of the sick princess, was a source of spiritual healing, that is, conversion to Christianity and the baptism of the children of the King of Ashur, Sennacherib. Sennacherib, mad with rage at this conversion, decides to kill his own children, who become martyrs to the faith, along with the 40 companions in the princely suite of Behnām and Sārah. The conversion of King Sennacherib would not have been possible without the intervention of Queen Shirin who, “to cry freely at the tomb of her children, had a seven-kilometre-long tunnel dug between her palace and martyrion built over the ‘pit’ of the martyrdom. Her husband eventually converted, exorcised by Mār Matta, so the whole family would be reunited in glory." Still today “everyone, from the Christians who live close to the monastery to the Arabs in the vicinity of Nimrūd believe firmly in the existence of this tunnel, and whenever even the smallest hole is found it is hailed as the entrance to the tunnel (...)" (source Jean-Maurice Fiey). This is how the epic of the conversion of “Assyria" to Christianity and then the building of its celebrated monasteries was created and passed down through the centuries to the present day.

More than a convent, the sanctuary of Mar Behnām was a martyrion, with a hostel for pilgrims visiting the site. According to local tradition, the tomb of Mar Behnām is also visited by many Muslims and Yazidis, particularly women, who ask the saint to intercede on their behalf for abundant crops and their own fertility or that of their livestock.

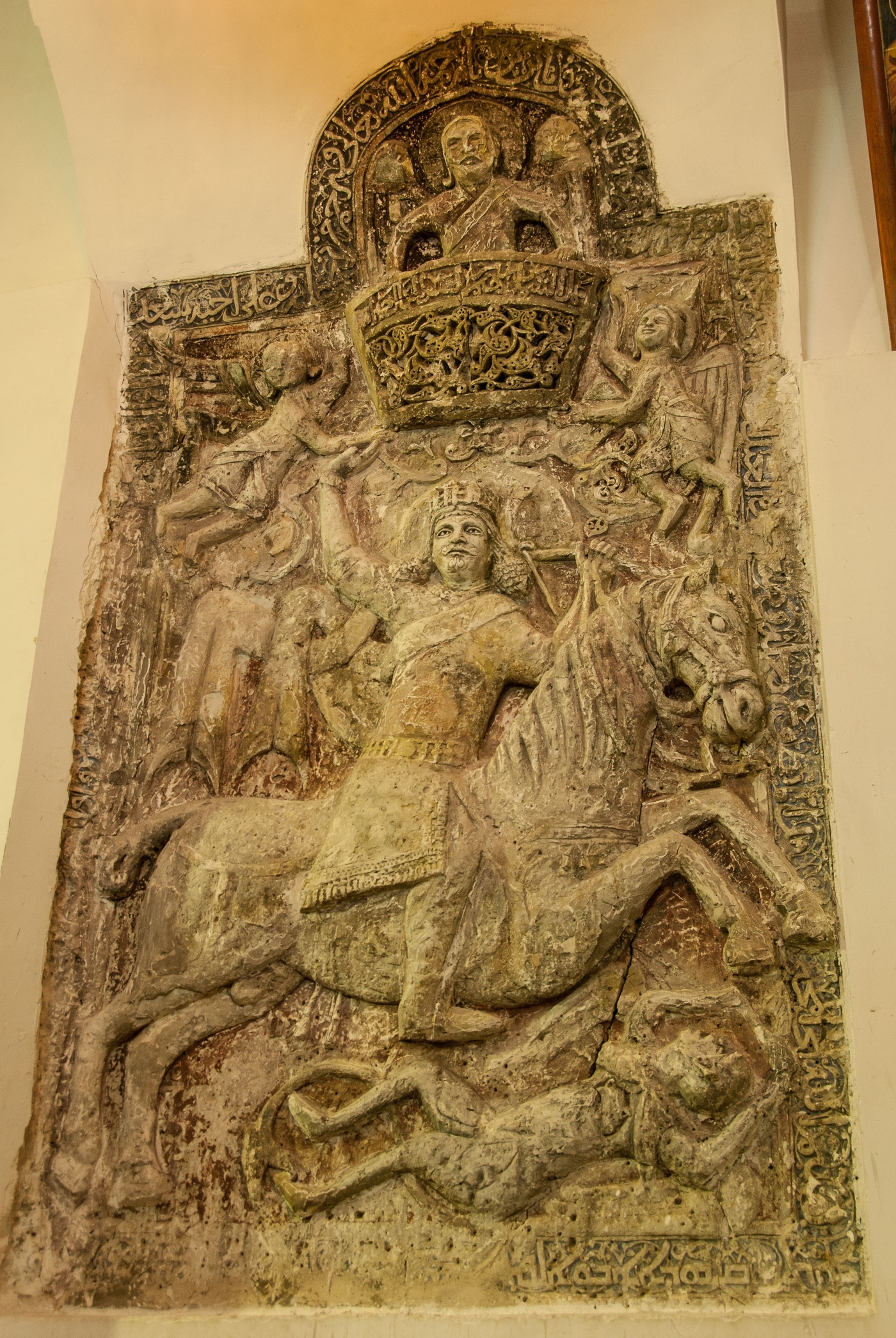

An outstanding heritage site destroyed by Daesh. The monastery of Mar Behnām still bears the traces of its renovation and ornamentation in 1164, brought to brilliant life by its elaborate decoration. The name of contemporaneous donors and artists can still be read on the walls, doors, door frames and lintels. The “masterpiece" for which the convent is perhaps best known is the finely carved high-relief of Mar Behnām on a horse trouncing the devil. This stucco work, set into the wall, was probably sculpted in the 13th century (source Amir Harrak), and was completely destroyed by Daesh, like the low-relief of Mart Sārah on the pillar opposite.

More destructive still was the use of explosives, in March 2015, to destroy the mausoleum (martyrion) of Mar Behnām, whose tomb, decorated with inscriptions in Syriac, Arabic and Uyghur, was dated to the year 1300, but could have been built as early as the 6th century (source amir Harrak).

Rebuilding of the mausoleum (martyrion) of Mar Behnām by the NGO Fraternité en Irak, co-funded by the Fondation ALIPH.

The architect and project manager of the restoration, Guillaume de Beaurepaire, tells us more: “The state in which the mausoleum of Mar Behnām was found in late 2016, following the withdrawal of Islamic State troops, was awful but reassuring at the same time. Although the images of the explosion leaked in 2015 made it look, at first sight, as if it had been destroyed beyond repair, once the rubble had been cleared, we realised that, from a heritage point of view, most of the important parts could be salvaged.

The complex can be divided into four parts: the entrance building, razed to its foundations, the access tunnels, partially destroyed and weakened beyond repair, the cistern or martyrium, of which the cupola has collapsed, and the arch opening into the tunnels; and finally a small vaulted room giving on to the martyrium, which has partially collapsed, but is mostly salvageable.

Some twenty containers of explosives did not explode, leaving a large section of the cistern walls intact.

Following the demolition of the hazardous areas, particularly the tunnels, the first bricks were laid in mid-January 2018. The same materials as the original building were used, including bricks recovered from ruined houses in Qaraqosh [Bakhdida], and air lime. The shape planned for the dome is not the same as it appeared in 2014. A decision was made to restore it to how it looked in the 1920s.

Great care was also taken to conserve and reposition the sculpted elements, which were reset in the niches of the cistern. The work was carried out by a group of French conservators."

The rebuilding of the mausoleum of Mar Behnām was completed in summer 2019.

The monastery of Rabban Hormizd in Alqosh

Founded in the 7th century, the monastery of Rabban Hormizd is one of the oldest in Iraq. Nestorian and wonder worker, Rabban Hormizd received visitors and pilgrims in search of a miracle cure in his hermitage. He died at the age of 90, 25 years after the founding of the monastery.

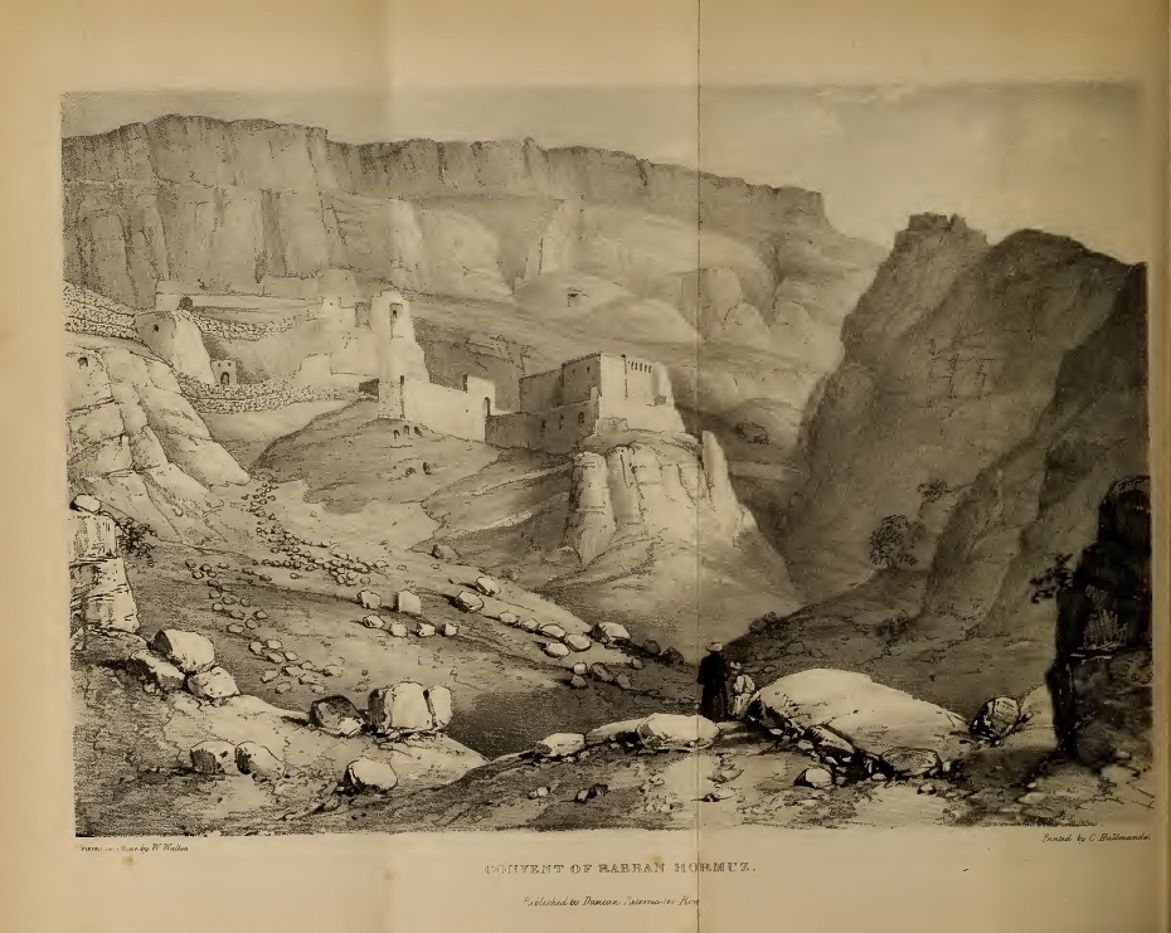

Perched on a cliffside at an altitude of 815 metres, 2 km to the northeast of the centre of the city of Alqosh, the monastery enjoys a remarkable location, 10 km from the eastern bank of the Tigris. To the south, it looks out across the desert plains of Nineveh. Mosul is only 40 km away as the crow flies. To the north, it abuts the mountainous massif, the border of ancient Assyria, which runs along the frontiers of present-day Iraq, Turkey and Iran. The monastery looks like a pearl in a jewellery case. The mountain onto which it gives is dotted with cells carved into the rock. Some are clearly very difficult to reach, while others have been gradually incorporated into the monastic building. This network of troglodytic cells underlines the importance of asceticism, as in many eastern monasteries, but also the resources it probably needed to ensure its own protection.

Over time, the monastery became the most important patriarchal see of the Eastern Church before becoming the see of the Chaldean Church. On 28 April 1553, Pope Julius III ordained Yohannan Soulaqa of Beth Ballo, senior monk of the monastery of Rabban Hormizd, as the first patriarch of the Chaldean Church.