- Home

- Knapped tools of Prehistory

- How were these objects made?

In this session, we chose to present sequences in the making of knapped stones "in the prehistoric style". They are the result of long research, begun more than a century ago, particularly in France by Léon Coutier, and later by François Bordes and Jacques Tixier, and in the USA by Don Crabtree. It should also be noted that although knapping methods (the layout of removals) are directly legible on the archaeological artefacts, the techniques are not. They must be "identified" by comparison with the marks obtained in modern knapping tests using different techniques (this is a major reason for the experimental lithic collection (“Technothèque”) of our laboratory: to serve as a reference for the recognition of techniques on archaeological artefacts). (In the same way, my colleague Valentine Roux has built up an important reference collection of experimental and ethnographic ceramics, in order to document the respective stigmas of forming and finishing ceramic techniques).

Thus, our practical knowledge of knapping techniques has been progressively enriched at the same time as techniques used on most of the prehistoric lithic knapped objects have been identified. We are therefore currently able to illustrate various prehistoric productions in a more or less "correct" way, which allows us, on certain aspects, to better understand their significance, as we will see in the 4th session.

Hard rock fracturing techniques

To begin this session, hammer in hand, we are going to reproduce here the two fracturing mechanisms of hard rocks :

- the split fracture;

- the conchoidal fracture.

The first creations: hard direct percussion

Carried out with the same technique (direct percussion with a hard hammer), certain flaking debitage methods, as Jacques Pelegrin explains, can be likened to simple "formulas" for arranging monotonous removals, but the Levallois method(s) involve the notion of predetermination and two different values of removals (flakes aimed at modifying the core, and flakes with a product value).

Shaping a biface

The making of a perfectly symmetrical biface with regular edges, such as was made nearly a million years ago in Africa and several hundred thousand years ago in Europe, requires an organic hammer and a sustained attention span. This is what Jacques Pelegrin explains in this video.

Sophistication in the Late Palaeolithic: debitage of Aurignacian blades, blade tools, bladelets

In this video, let's find out how Aurignacians intentionally used direct organic percussion to detach blades to make their main tools, such as end-scrapers and burins, as well as delicate bladelets (or “microblades”).

Sophistication in the Late Palaeolithic: debitage of Gravettian blades, and Gravette points

To make their Gravette points (according to the eponymous site of Dordogne), you will understand in this video how the Gravettians practised a very careful blade debitage.

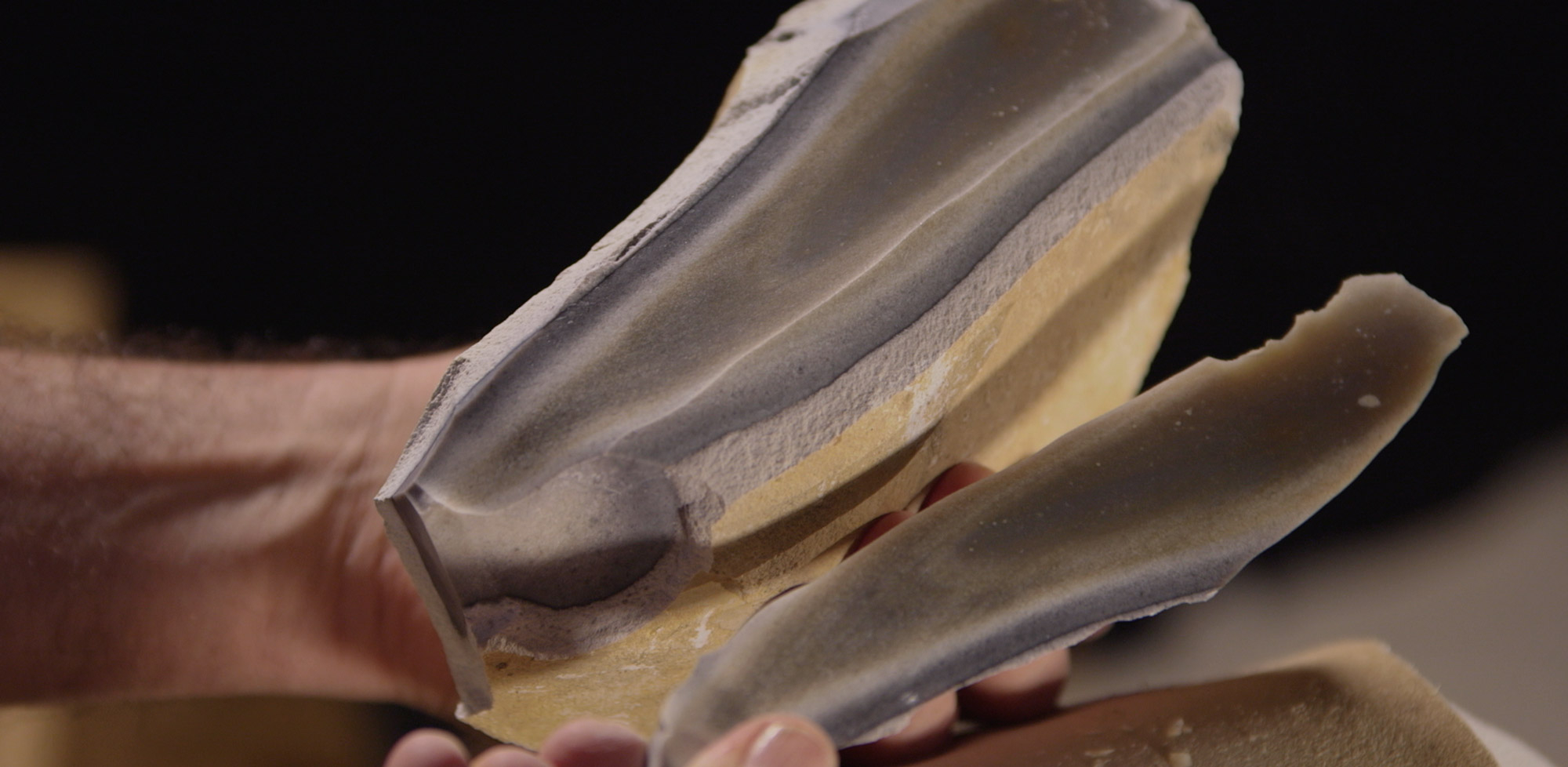

The laurel leaf and the end of the Late Palaeolithic period

Small or large, flint laurel leaves of the Solutrean, nearly 20,000 years ago, represent a remarkable "investment" as Jacques Pelegrin explains in the following video. On the other hand, the end of the Late Palaeolithic (around 12,000 BC) saw a clear simplification of stone tools.

Innovations in recent periods: indirect percussion

Appearing in recent Mesolithic times in Western Europe, but perhaps in the forefront of the Neolithic movement that would soon cross the Mediterranean and Central Europe from the Near East, indirect percussion for blade debitage spread with great success, as you will understand in this video.

Innovations in recent periods: pressure debitage

From invention to innovation, as Jacques Pelegrin explains in the video below, pressure debitage has gone from the making of tiny microblades to that of large blades in several regions of the world (Anatolia, Mediterranean and Central Europe, North Africa, the Levant, China, Mesoamerica...).

Bibliographical references

- Piel-Desruisseaux, J.-L. 2016. Outils préhistoriques, de l’éclat à la flèche. Paris: Dunod. 7th edition, 344 pp.

- Pelegrin, J. & Texier, P.-J. 2004. Les techniques de taille de la pierre. In: Les Dossiers d’Archéologie Special Issue 290: 26–33.

Online resources

- Flint experiment with long blades. Archaeologist Jacques Pelegrin (CNRS), 15 min. Réalisation Ole Malling. Filmed at the Historical-Archaeological Research Centre at Lejre, Denmark, 1993–94 (now Sagnlandet Lejre). https://vimeo.com/178391132

- Observations sur la taille et le polissage de haches en silex. Jacques Pelegrin. In: Produire des haches au Néolithique : de la matière première à l’abandon. Actes de la table ronde de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 16 et 17 mars 2007, musée d’Archéologie nationale. Textes publiés sous la direction de Pierre-Arnaud de Labriffe et Éric Thirault. Paris, Société préhistorique française, 2012 (Séances de la Société préhistorique française, 1): 87–106. Download PDF

- About INRAP excavations at Lhéry (Late Mesolithic): demonstration of indirect percussion debitage and toolmaking. La taille du Silex au Mésolithique final avec Jacques Pelegrin. 7'38". https://www.inrap.fr/tailler-le-silex-9508