The underwater archaeology of the Normandy landings

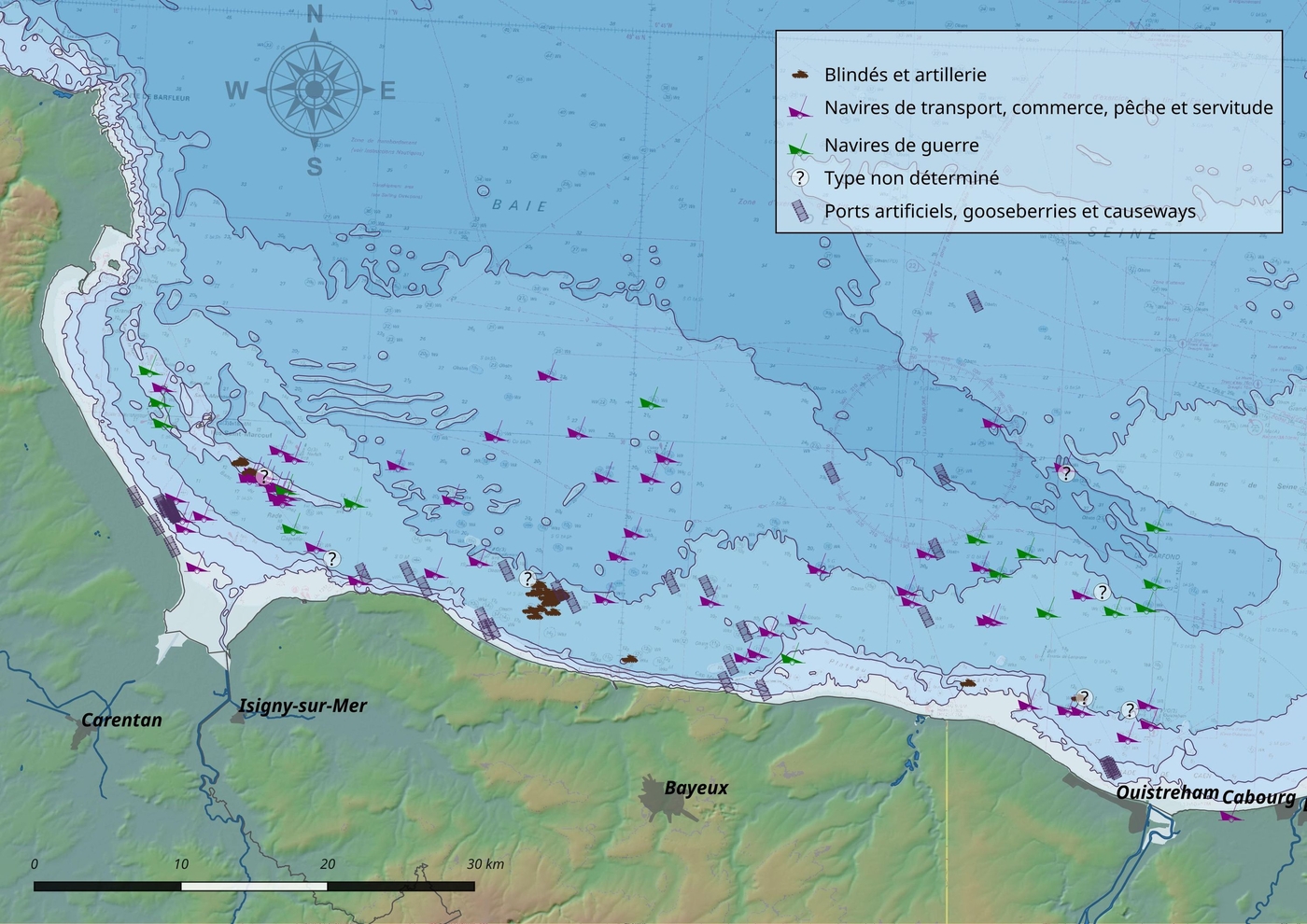

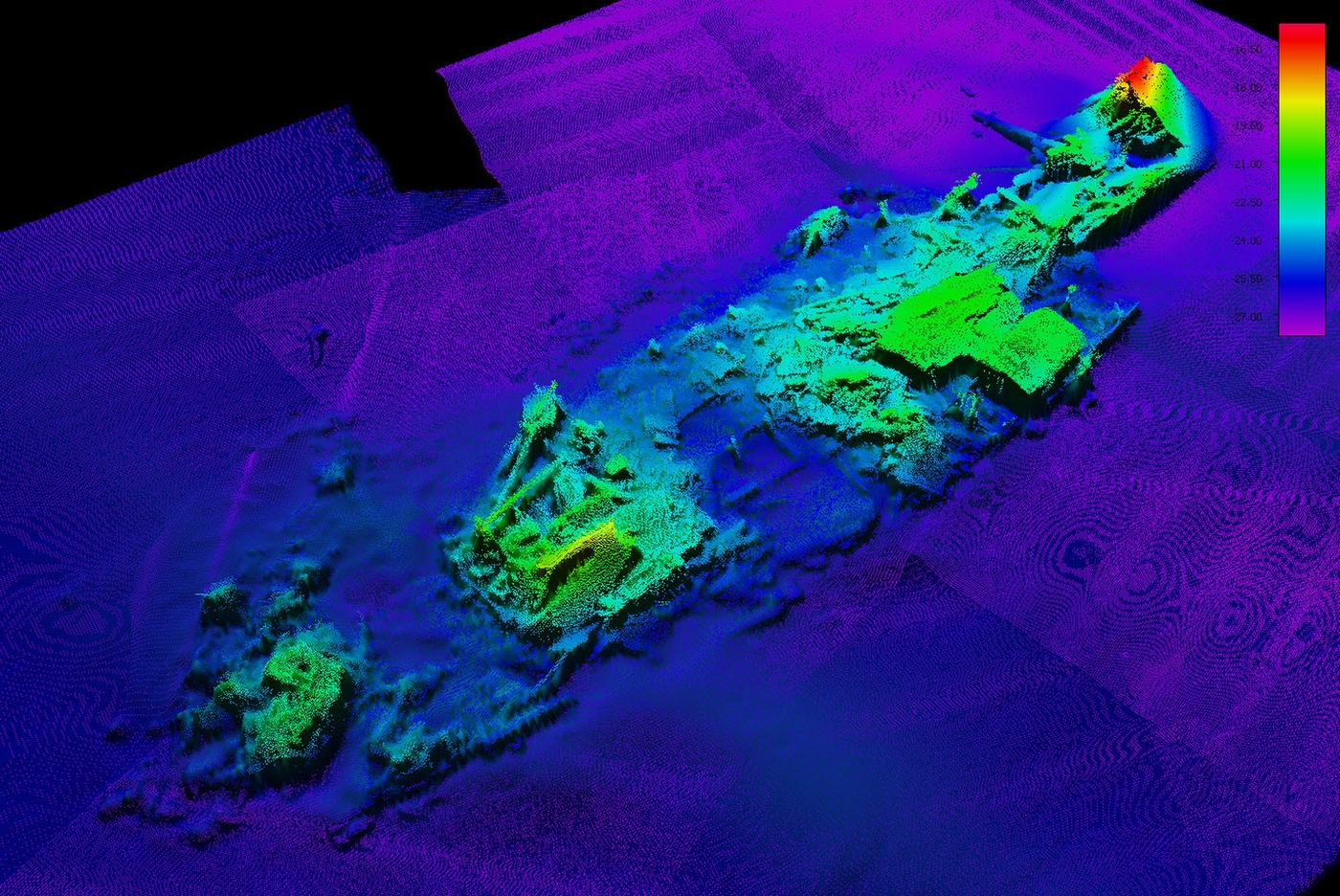

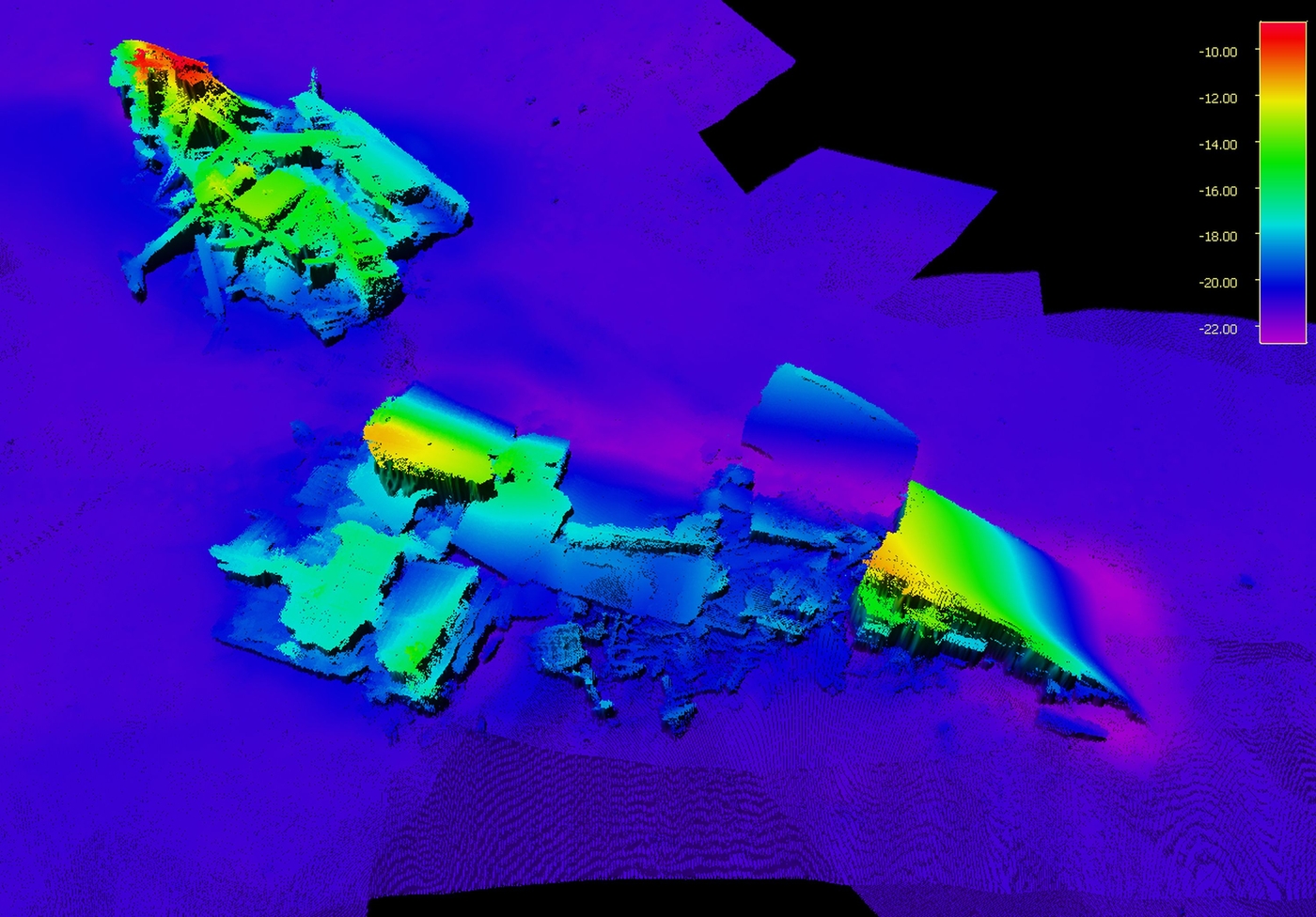

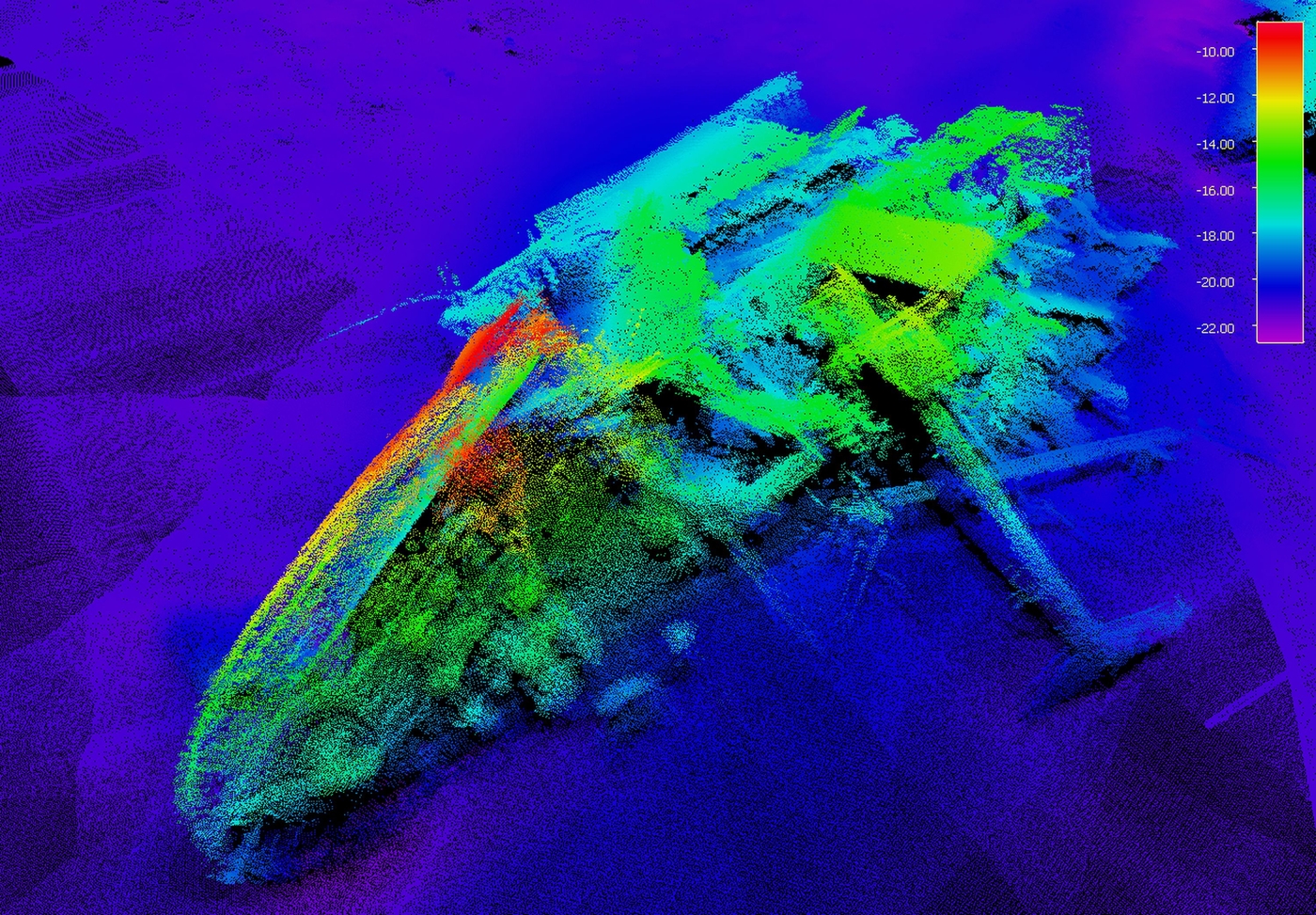

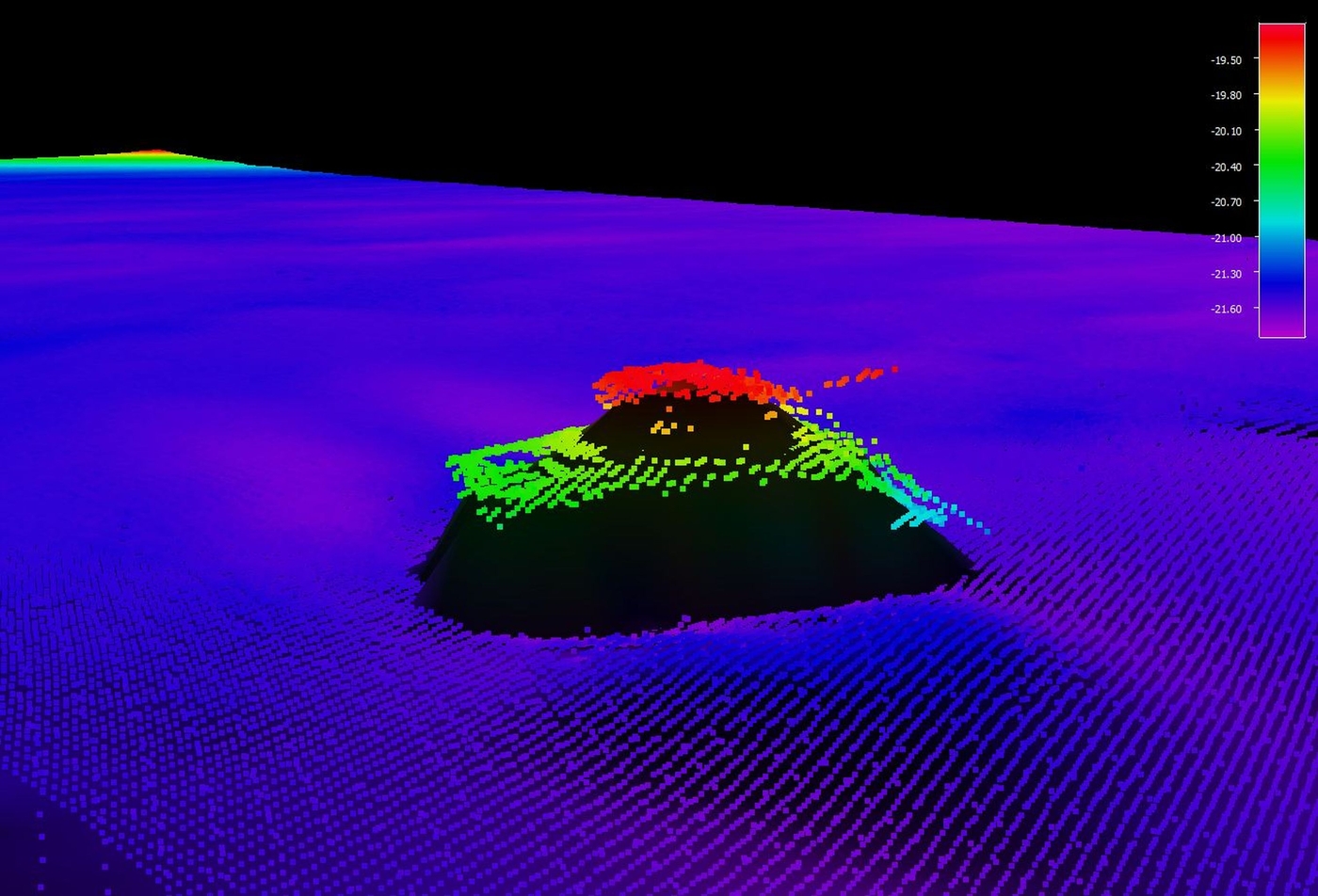

Off the coast of the Normandy landing beaches, the bed of the Baie de Seine conserves one of the world’s largest areas of underwater remains. Some 150 wrecks of ships, landing craft, tanks and the remains of artificial harbours, attest to the variety of equipment used by the Allied Forces.

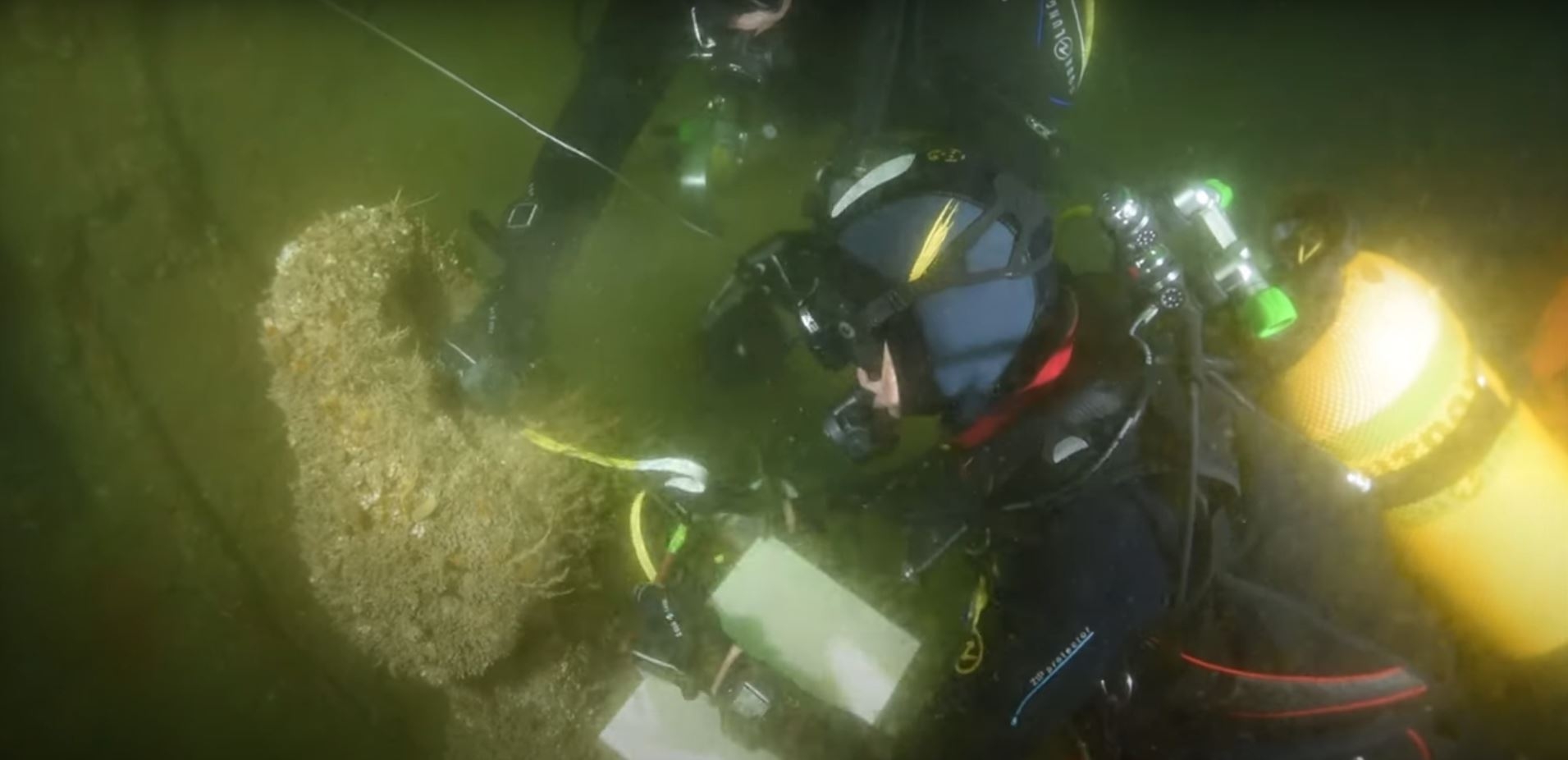

Since the 2000s, divers, hydrographers, historians and archaeologists from the US, Britain, Canada and France have worked to locate and study the maritime remains of the Normandy landings.

An inventory of some 150 maritime sites

Plans to inscribe the remains of the Normandy landings on the World Heritage List, headed by the Région Normandie, provided an opportunity for the Department of Underwater and Submarine Archaeological Research (DRASSM, Ministry of Culture) to thoroughly review and check this data. An inventory of some 150 maritime sites was drawn up based on an analysis of the existing data and new research carried out in the field. It brings to life the variety of equipment used by the Allies to organise the biggest maritime landing ever made.

New title in the Grands sites archéologiques collection

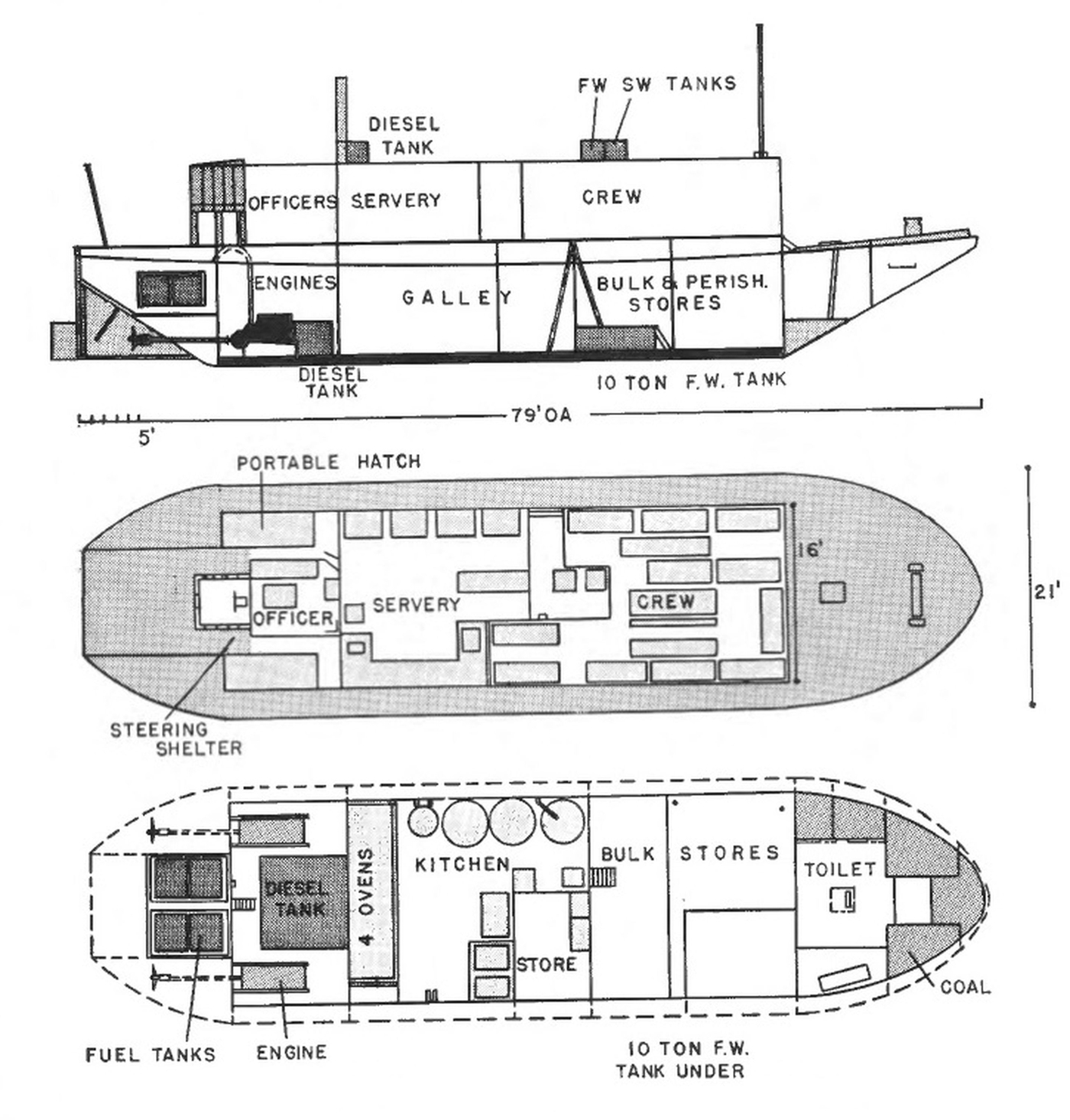

The creation of a title in the Grands sites archéologiques collection aims to make available to all, divers and non-divers, beginners and seasoned archaeologists, this body of finds that today constitutes one of the world’s largest groups of underwater remnants. The historical presentation draws attention to the fact that the Normandy landings were primarily a maritime operation that began on 6 June 1944 and lasted until the end of 1944. It will also explain the threats to this heritage and the specific measures taken to help study them. It will also highlight the typological variety of the remains conserved and what they reveal in terms of the engineering and logistical innovations developed by the Allies.

Research project

This corpus was brought together and funded by DRASSM (French Ministry of Culture), with ad hoc support from the Région Normandie. It brought together archaeologists from DRASSM, the ADRAMAR non-profit organisation and the company Ipso Facto as well as volunteer divers, photographers and sailors. The data used were partly sourced from works published by the divers from Caen Plongée. They were also partly sourced from operations carried out by the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) of the US Navy, the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO), and the companies MC4 and Antéa.