The Prehistory of Limpopo

The first anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens, appeared on the African continent some 300,000 years ago, but it was only 60,000 years ago that they reached the Eurasian continent and settled it permanently. The success of this dispersion is down to several factors and behaviours that gave modern humans an advantage as they explored and adapted to their environment.

Our archaeological research on the African continent aims to understand where, when and how these new behaviours appeared. Our work has been focused on South Africa since 1998, building on the results of the Diepkloof project, which helped reveal the outstanding Prehistoric heritage of this world region.

The emergence of "modern" behaviours

What sets apart the South African sites is the early appearance of "modern" behaviours, starting some 100,000 years ago, which take the form of innovative techniques, including the heat treatment of rocks and the application of pressure to shape tools, the first symbolic expressions such as bead production and use, and the first geometric motifs. These new practices and forms of knowledge mark a new stage in the history of hunter-gatherer societies.

However, this scenario of cultural change, from the Late Pleistocene to the Holocene, is neither linear in time nor uniform in space, revealing the "bushy" nature of this evolution. Excavations at the Bushman Rock Shelter and Heuningneskrans sites cover more than 120,000 years of history and shine a unique light on the history of the societies formed by modern humans close to the waterfalls of the Blyde River.

Two neighbouring shelters

The project in the valley of Ohrigstad is based on the excavation of two neighbouring sites: the Bushman and Heuningneskrans shelters. Both shelters are located less than 4 km from each other and represent two impressive sedimentary sequences with respectively 8 metres of archaeological deposits conserved in the Bushman shelter and more than 6 metres of deposits in the Heuningneskrans shelter.

This provides a rare opportunity to work jointly on both archaeological sites and offers multiple advantages from a disciplinary point of view. Since the Bushman and Heuningneskrans sequences are complementary and to a certain extent contemporary, archaeologists have been able to compare and integrate the varied cultural and environmental archives from the Late Pleistocene to the Holocene.

These archaeological archives are especially well preserved in the form of animal bones, fragments of sedimentary DNA and botanical remains - coal and seeds. Besides the quality of the preserved remains, the shelters stand out for their high-resolution sedimentary records, enabling archaeologists to accurately reconstruct the chronologies of human occupation, activities and environments. The archaeological discoveries shed light on the history of the Later Stone Age and then the Middle Stone Age, shifting the scientific focus towards the origin of the hunter-gather peoples who still occupied the subcontinent several centuries ago. The archaeological heritage of South Africa, and the nature of its records, has informed our models of the evolution of human societies and drives our search for the universal in the unique.

A multi-disciplinary project

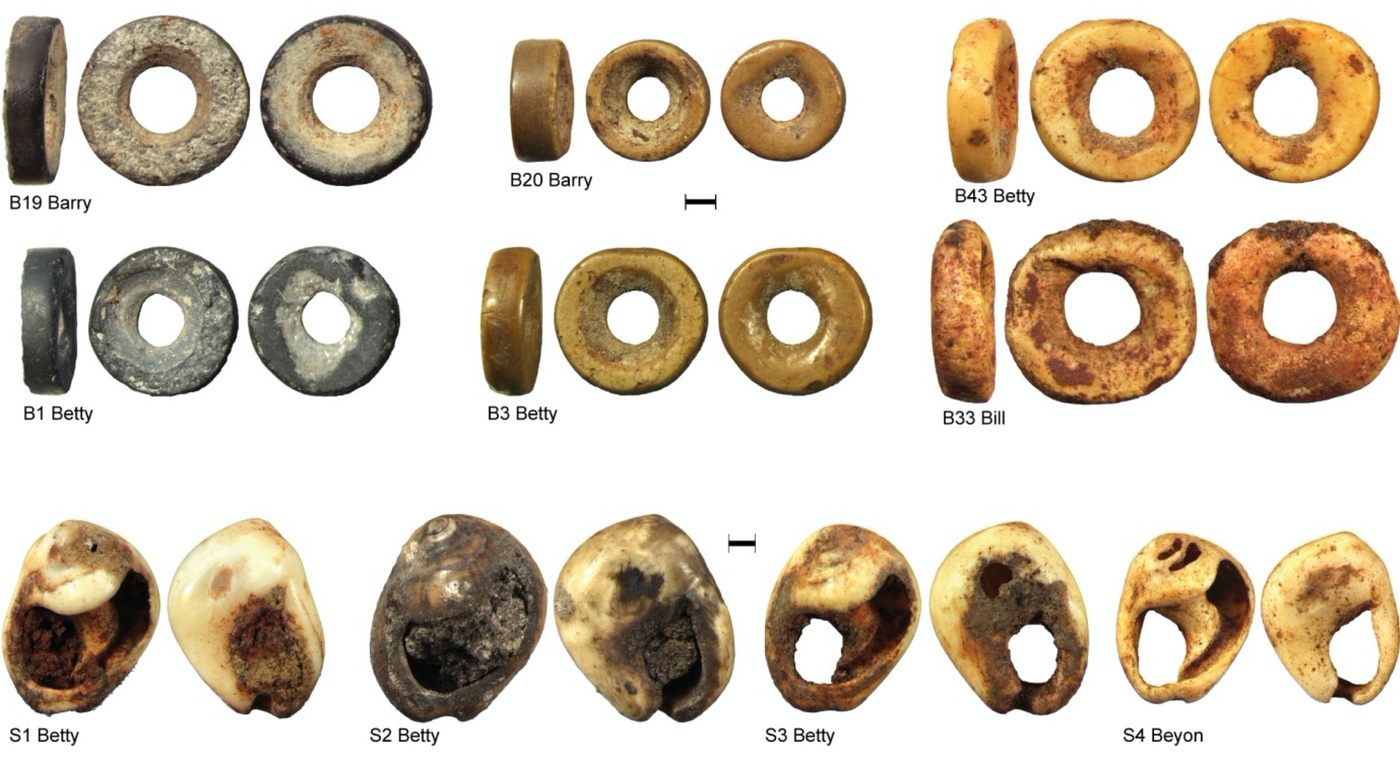

The research project is led by specialists from African and European institutions. The project was naturally organised around the nesting of field and laboratory disciplines, from understanding site formation processes to the timeline of human occupations calculated using radiocarbon and luminescence dating. The archaeological finds allow us to reconstruct in detail palaeoenvironments and subsistence strategies by studying botanical - coal, seeds and phytoliths - and faunal remains. These finds also provide the means to broadly reconstruct the cultural traditions of human groups through a reading of technical systems - lithic and bone - and registers of symbolic expression - adornments, mortuary goods, and wall groovings. Inter-site comparisons shed light on the cultural geography of the sites, which also draws on evidence of long-distance mobility. The discovery of several shell beads (Nassariuskraussianus) originating on the Mozambican shores of the Indian Ocean attest to contact, movement and exchange over a distance of 200 km.

A field school

The valley of Ohrigstad is in north-eastern South Africa near the borders with Zimbabwe and Mozambique and the coastal corridor linking the south and east of Africa. This geographical location is one of the reasons why we chose to study this region, in order to free our discussions from administrative restrictions and promote the circulation of ideas and people across southern Africa. Within this perspective, an accent was placed very early on the training and mobility of African students, with the involvement of students from South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Zambia. These students come to familiarise themselves with the methods and techniques of prehistoric excavation, and explore collaborative and multi-disciplinary approaches to work. Every year since 2014, one or two African students have broadened their field experience by joining the excavation on the Palaeolithic site of Les Prés de Laure, in southeast France.

The project is supported by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs on the advice of the Excavations Board (Commission des fouilles).