Ancient metallurgy in West Africa

The proliferation of new materials has undermined the importance of iron in our lives today. But it was once used in every area of life, from agriculture to weaponry and decoration. Although metal production has been practiced in Africa for more than 3,000 years, little is known about its impact on pre-industrial societies.

By identifying production districts, distribution networks and places of consumption, the aim of our archaeological research is to understand the role of iron as a material that shaped medieval and modern societies. Since 2014, a multidisciplinary team of archaeologists, geologists and archaeometrists has been carrying out research in Togo and Benin.

Iron production in West Africa

From the 8th century and throughout the 2nd millennium CE in particular, there was an explosion in the number of iron production sites in Sahelian and sub-Sahelian Africa. Thanks to a subsoil rich in iron ore, practically every region of Africa has one or more metallurgy workshops. Some of them produced large quantities of metal and became major specialist centres as attested by the remains of large quantities of production waste known as slag.

The intensification of iron production did not happen at the same time in every region. Excavations of iron-production sites in Bassar (Togo), Atakora and Mono (Benin) provide a unique opportunity to develop a more detailed understanding of the economic development of these workshops and to trace the distribution networks they supplied.

From ore to hoe

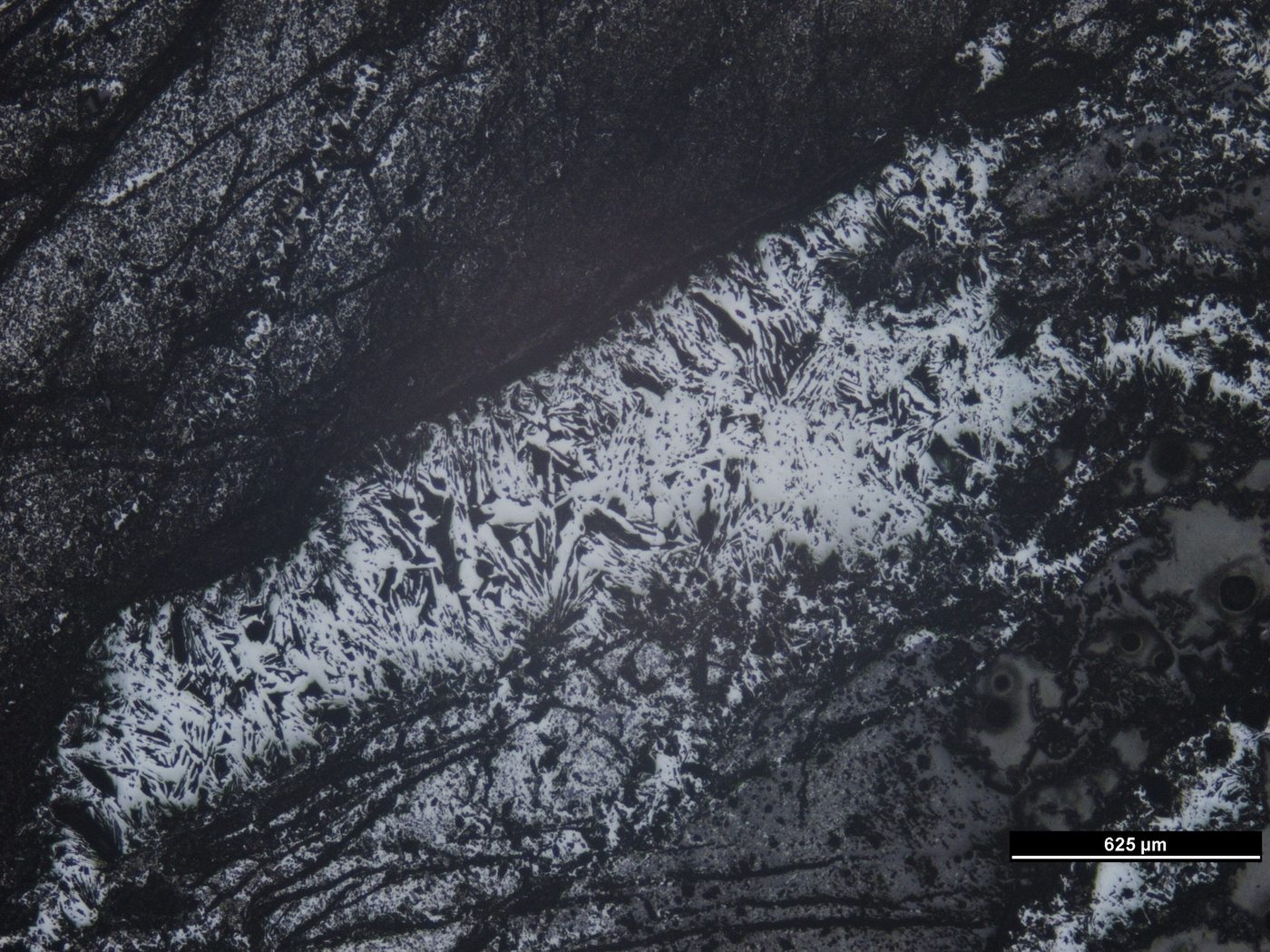

The characterisation of iron ore deposits and metallurgy techniques is central to our project since it feeds into research on the economy and the trade in metals in the ancient world. Tracing the routes taken by the metal to sites where it was going to be used is essential to efforts to reconstruct the history of a society and the influence of its activities on its own development.

This information will be supplied by the identification of the geological deposits that provided the ores, the minerological and chemical characterisation of the raw materials (ore, kiln clay, etc.), waste (slag) and products (the iron) in the chaîne opératoire, from mine to object, and the excavation of the sites where this iron was used.

Thanks to archaeology, archaeometry, a discipline at the interface between archaeology and the “hard" sciences, and geology, it will then be possible to understand how the raw materials (particularly the iron ore) were obtained, estimate the productivity of the activity, reconstruct the distribution networks for metal products in different regions, and understand the economic history of these civilisations.

The questions of supply and trade are determined in conjunction with historians, archaeologists and ethnologists, whereas the answers to them are based on the methods that fall within the scope of the earth sciences. The challenge of this project is to provide initial answers to these questions within the context of the intensive iron production that developed in West Africa during the medieval and modern periods, perhaps in tandem with the transatlantic trade and the slave trade.

Two countries, several ancient centres of iron production

Coastal countries, Togo and Benin stretch for more than 700 kilometres from north to south, encompassing the Guinean, Sudanian and Sudano-Sahelian regions. This variety of landscapes is reflected in the complexity of the history of their settlement and, accordingly, in the diversity of the metallurgy techniques developed there.

In Togo, research into the ancient metallurgy of iron, which was focused on the region of Bassar but also practiced in other areas (Tado and Dapaong), has highlighted the importance of this activity. The history of iron here starts at a relatively early stage. In Bassar, it begins in the 5th century BCE. Following a long hiatus, it resumes with a period of intensive activity from the end of the 13th century to the early 20th century CE. In the ancient city of Tado, iron production lasts only three centuries, from the 12th to the 14th centuries CE. Despite the large quantity of metallurgical waste discovered in the region of Dapaong, before archaeological excavations are carried out, it is impossible to date and characterise these remains.

In Benin, extensive research has also been done into the ancient metallurgy of iron. Carried out across the country, it has highlighted four regions where metallurgy played a key role in the development of local societies: Mono, Atakora, Borgou and Dendi. For the moment, the history of iron in the regions of Mono and Dendi only appears to date to the early or second half of the first millennium CE. Its production became more widespread over the centuries. In Mono, metallurgy exceeded local needs between the 13th and 17th centuries. It was still operating and prospering in Atakora and Dendi until the early 20th century.

With a view to studying the trade and distribution of iron along the west coast of Africa, our research project will focus in particular on two regions where metallurgy underwent a period of intensification: Bassar (Togo) and Mono (Benin). As part of a broader analysis, other areas where metallurgy was practiced such as Tado and Dapaong in Togo and Atakora and Dendi in Benin will form the subject of university research carried about by Master and doctoral students for their dissertations.

A training project for researchers from France, Benin and Togo

Besides this scientific research, our project also aims to expand archaeological research in Benin and Togo by helping train a new generation of archaeologists and protecting and promoting this rich tangible and intangible heritage that is too often ignored.

Our project provides students from Togo and Benin with the opportunity to take part in an annual one-month archaeological traineeship. The creation of a joint training module shared by the universities of Kara, Lomé (Togo) and Abomey-Calavi (Benin) will boost the mobility of students and lecturer/researchers in these neighbouring countries and give greater impetus to the higher education dimension in Africa. For the students, it is an opportunity to develop intercultural and professional skills and to smooth their path towards an academic career. For lecturers and researchers, it opens up the possibility of acquiring knowledge and know-how based on their experiences abroad and to strengthen ties between African universities. Moreover, the involvement of French researchers will help broaden and complete the curriculum and interconnect various disciplines.

We believe that this type of training will help develop the archaeology sector and its related skills. Togo and Benin have a rich heritage. Its knowledge, preservation and promotion are a matter of national pride. At stake are the country’s image abroad and the new cultural and economic activities created as part of a sustainable development approach.

Project supported by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs on the advice of the Excavation Committee (Commission des fouilles).

Useful link

- Introduction to the programme on the website of the Laboratoire Traces

- Documentary: Bitchabé le village des forgerons (Bitchabe: village of smiths)

- Documentary: Fer ancien, archéologie expérimentale au Togo (Ancient iron: archaeological experimentation in Togo) (CNRS)